The announcement that the Sun newspaper was going to drop its topless Page 3 girls had the usual suspects all in a tizzy.

Long a target for feminist ire, the once-symbol of the sexual liberation of the 60s and 70s when women were burning their bras has become, for some, a symbol of the oppression of women by men.

Comparisons are convolutedly made to Muslim women who insist on covering their faces with the niqab, and slogans such as “Je suis page 3” are touted with typical taste and tact. Eloquent odes to verbosity richly marbled with pithy quotes from feminist pugilists are penned and published condemning such anachronistic sleaze.

Comparisons are convolutedly made to Muslim women who insist on covering their faces with the niqab, and slogans such as “Je suis page 3” are touted with typical taste and tact. Eloquent odes to verbosity richly marbled with pithy quotes from feminist pugilists are penned and published condemning such anachronistic sleaze.

Dressing up in a way that men might find appealing makes women look inferior and submissive to men, comes the refrain, all you ladies throwing on the glad rags and tottering off to Coppers for a few scoops take note, tut tut.

So when word was spread that this iconic relic of masculine power was being dropped, bottles of Beaumont des Crayeres Grande were popped, glasses were raised, and toasts were made to the inevitable collapse of the ever looming patriarchy.

Protestors at the “No More Page 3” campaign headed by Lucy Ann Holmes were delighted that their online petition had swayed the likes of media tycoon Rupert Murdoch, a heady rush and a solid result for such strenuous efforts.

Across the water The Guardian joined in the celebrations, calling it a “landmark decision”.

Susan McKay in the Irish Times trilled that it was a “sweet victory” for feminists, gleefully asking us “why stop at page 3?” and hinting heavily that such provocative displays were at least partially responsible for inciting men to rape, presumably in much the same way that violent video games are responsible for the wave of street battles and drive by shootings gripping our nation at the moment.

Except of course no such thing is happening.

And neither, as it turned out, was the Sun cancelling its venerable Page 3 tradition. As Dylan Sharpe, the public relations head for the tabloid tweeted shortly after the reports of Page 3’s demise had finished their feverish circulation,

| I said that it was speculation and not to trust reports by people unconnected to The Sun. A lot of people are about to look very silly… |

It seems likely that he’s got a stellar career ahead in PR! Yes, the whole thing was a marketing stunt designed to boost sales of the newspaper, and it worked just as it was intended to. Those who wanted to do away with Page 3 ended up promoting it.

Disappointment was palpable amongst the self appointed defenders of womens’ dignity, with Suzanne Harrington of the Irish Examiner writing a bizarre and somewhat convoluted piece which included such sentiments as:

| This particular fat, ugly, joyless, jealous, feminist fanatic is lost for words. Nice one, sister. |

But really, when we get down to it, what is sexual objectification and why is it such a big deal for feminists? After all shouldn’t they be in favour of women being allowed to do what they like with their own bodies?

Sexual objectification as it is most commonly used means treating someone as if they are a thing, the subject-object dichotomy where a subject acts, and an object is acted upon. Thus, goes the theory, by objectifying women men remove their ability to act and hence their power.

It means essentially that regardless of how the person is viewed aesthetically or sexually, they are treated or thought of with a similar amount of respect and regard as one would treat a thing or object.

The feminist philosopher Martha Nussbaum states that a person might be objectified if they’re treated like they have one or a selection of the following properties:

- Instrumentality – as if a tool for another’s purposes

- Denial of Autonomy – as if lacking in agency or self-determination

- Inertness – as if without action

- Fungibility – as if interchangeable

- Violability – as if permissible to damage or destroy

- Ownership – as if owned by another

- Denial of Subjectivity – as if there is no need for concern for their feelings and experiences

Now, it hardly seems credible that the treatment of a nude model falls under any different a selection of those conditions with any more severity than any waiter, pizza delivery person, or supermarket cashier.

Surely a photoshoot in Playboy treats its subject with no less concern for her feelings, as if she is no more or less interchangeable, as no more a tool, as no more inert or owned, and certainly no more permissible to harm, than a hotel treats its staff.

In fact, it seems likely that a model is seen as being considerably less interchangeable, owned, inert, and lacking agency. If dining in a restaurant, do we pay much attention to the waitresses’ thoughts, experiences, concerns, or emotions any more or less than those of a pole dancer’s in a strip club?

The manager of a supermarket would no more wonder about a cashier’s political persuasions than the owner of a soft porn magazine would about one of its models. We objectify others all the time, because it is simply not possible to deeply care and thoughtfully consider each and every person who provides a service for us or works for us.

This is certainly not problematic, but simply natural. Objectification is not a problem. It is a healthy way which we deal with everyday life.

So what’s the difference here? Why is the objectification of models or strippers so often highlighted, but not the objectification of pizza delivery boys or waitresses? Why does it seem to be the “sexual” aspect that is so problematic?

An argument which regularly makes an appearance relates to the idea that sexual objectification portrays women as aesthetically akin to objects, implying that when you look at someone and only focus on their sexuality you are viewing them as an object or thing. It implies that a sexualised image of a woman, in say, Playboy, shows the woman as an object.

However when you look at a person sexually and only sexually, you may have a very impersonal relationship with them, but you are not sexually viewing them as an object, as “objects” are intrinsically not sexual (an argument that individualist feminist Wendy McElroy makes). People are not typically sexually aroused by cabbages or chairs.

Even if an actual object is to be made to appear sexual (such as sex dolls), it has to be given the resemblance of a human in order for it to be sexually attractive. Or, in other words, for an “object” to be viewed as sexually attractive, it has to be designed so that it no longer appears to be an object.

Therefore, the property of something being or appearing to be an object makes it intrinsically not sexually appealing, so to say that when someone is being displayed solely for their sexual appeal, this portrayal makes them seem like an “object” is simply fallacious, as “objectuality” is the antithesis of sexuality.

Sexual objectification may be very impersonal, but it does not make sense for it to literally mean the portrayal of women as objects.

This may seem as though it’s simply a question of linguistic semantics, but that’s not the case. When discussing subjective opinions it’s absolutely necessary that the words or terms you use have a definite, clear, concrete meaning, especially a term such as “sex object” which has such currency in society today.

If a term is both nebulous and emphatic, then it is hyperbole. If it is used as axiomatically and prolifically as “sex object”, then it enters the realm of being propaganda.

Then there’s the oft repeated notion that porn, erotic images, glamour photos, or stripping are correlated with rape.

Where is the evidence for this? And if people believe “sexual objectification” causes rape, does that mean they believe that sex workers and lap dancers cause rape because their work involves being “sexually objectified”? Do girls who post nude pictures of themselves online cause rape? Can erotic fiction cause rape? Do models cause rape? Perhaps girls in short skirts and crop tops cause rape?

This all sounds rather akin to victim blaming and slut-shaming, not to mention puritanical and controlling. Maybe we should police and regulate women to ensure they do not cause themselves to be raped! Aren’t rapists the only ones at fault? Shouldn’t women be able to live in a world where they can choose to do what they want with their bodies without fear of being blamed for causing sexual abuse?

People should not incur blame for actions that others independently commit unless they intentionally tried to incite them. Such an idea undermines the very foundations of justice.

Salman Rushdie should not have received blame for the violence in Pakistan that ensued after the release of The Satanic Verses. Christopher Nolan shouldn’t be blamed because some maniac watched The Dark Knight and shot people. And a stripper should not bear the blame for sexual assault.

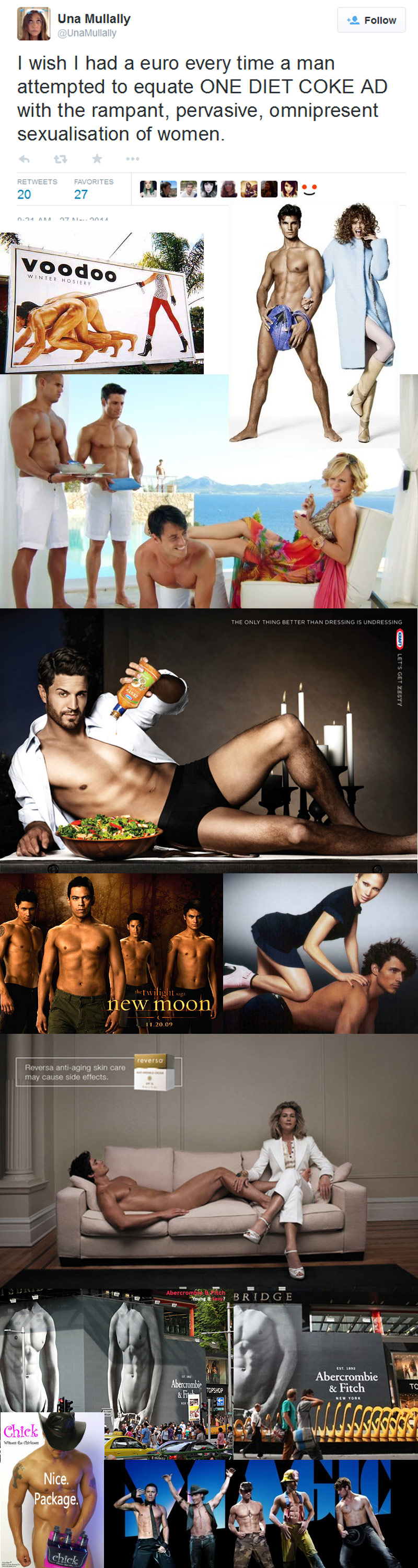

But let’s say for the sake of argument that sexual objectification is a real and negative thing, as resident Irish Times feminist Una Mullally firmly believes.

Why wouldn’t it affect men too?

At the end of the day, men shouldn’t feel ashamed, afraid or guilty for admiring the female figure, and neither should women feel bad about admiring the male form. It doesn’t hurt anyone except people looking for an excuse to be hurt.

[Ed. note: This post originally appeared here and is reprinted with permission. MHRI wishes to thank the co-author of this article, prominent blogger Red Blooded Liberalism for their excellent analysis of objectification.]