There has been a good deal of talk lately about women’s spaces being invaded by biologically male persons identifying as women. Some women’s campaigners claim that the trans phenomenon constitutes an attack on womanhood itself, an attempt to “erase” women and replace them with men who perform womanhood. Some even call it a new form of patriarchy.

But well before women had their single-sex spaces threatened, something similar had already happened to men. Beginning in the 1970s, men’s spaces were usurped, their maleness was denigrated, and policies and laws forced changes in male behavior that turned many workplaces into feminized fiefdoms in which men held their jobs only so long as women allowed them to. The very idea of an exclusively male workspace or club—especially if it was a space for socializing (not so much if it was a sewer, oil field, or shop floor in which men did unpleasant, dangerous work)—came to be seen as dangerous. In light of the recent furor over single-sex spaces for women, it is useful to consider the source of some men’s justifiable apathy and resentment.

At my new academic job in the late 1990s, a woman who had been the first female historian hired into her department used to tell a story she’d had passed on to her from a male colleague. After the decision had been made to hire her, one of the historians said to another somewhat dolefully, “I guess that’s the end of our meetings in the urinal.” The joke ruefully acknowledged, and good-naturedly accepted, the end of their all-male work environment.

Though this woman didn’t have any trouble with her male colleagues, who welcomed her civilly, she told the story with an edge of contempt. Even thoroughly modern men, the story suggested, held a foolish nostalgia for pre-feminist days.

But was it foolish—or did the men recognize something real?

No one thought seriously, then, about the disappearance of men’s single-sex spaces. The idea that men and boys need places where they can be with other men (defended, for example, in Jack Donovan’s The Way of Men) would have been cause, amongst the women I knew, for scornful laughter. In 2018, anti-male assumptions had become so deeply entrenched that the female author of a Guardian article titled “Men-only clubs and menace: how the establishment maintains male power” simply could not believe that any decent man could legitimately seek out male-only company.

***

The story of women’s appropriation of male space has almost always been presented as an unqualified good. Implicit in the story is the assumption that male spaces did not offer anything positive: on the contrary, they were alleged to be harmful by their nature to both women and men, though especially to women. If men’s needs were mentioned, which they usually weren’t, it was alleged that men would only benefit through contact with women’s much-touted superior empathy, team-building, and communication skills.

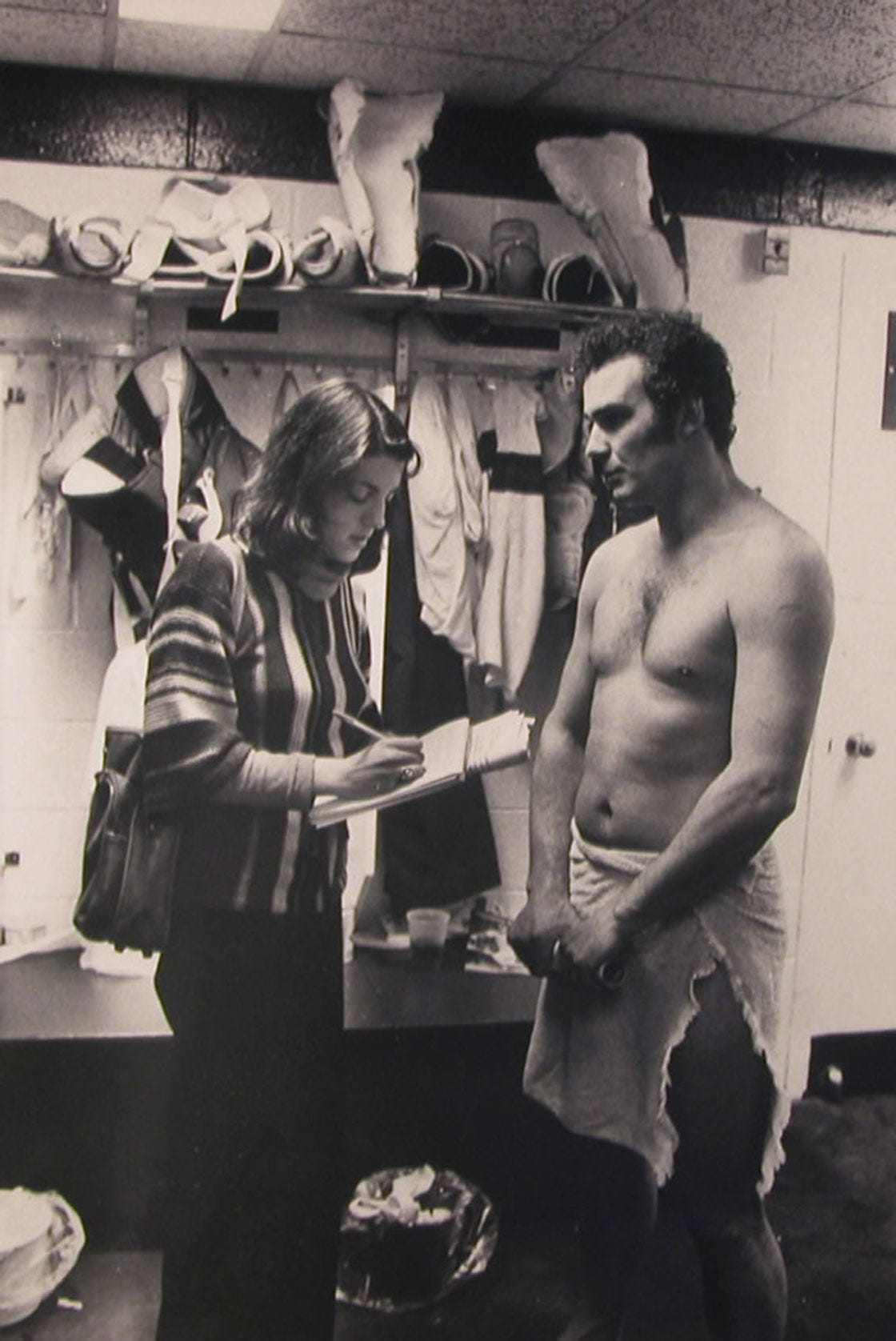

An article from Sports History Weekly showcases the stark clarity of the standard narrative. In 2018, an article titled “Locker Rooms Open Up to Female Journalists” told of the victory achieved 40 years previously when, in 1978, “a federal judge ruled that women reporters could not be barred from interviewing [professional sports] players inside the locker room.” The history of female reporters’ entry into men’s change rooms was framed as the triumph of women’s professional dedication over male chauvinism. One of the first two journalists to interview hockey players in the post-game locker room (in 1975), is said to have asserted, admirably if a trifle insincerely, “I’m not the story, the game is the story.”

Indeed, the picture chosen to accompany the story shows the reporter, Robin Herman, bent over her note pad, unselfconsciously focused on recording “the story.” Close by her side, a man scantily clad in his briefs is just getting to his feet, but the reporter’s attention does not waver. The message of the picture seemed undeniable: skilled female professionals posed no (sexual or other) threat to male players, so only an old prude or a sexist boor would deny women access.

Prudish was the image presented of Bowie Kuhn, Major League Baseball’s Commissioner, who had tried unsuccessfully to stem the tide of progress. When he prevented individual baseball teams from allowing women to report inside players’ dressing rooms, one of the reporters, Melissa Ludtke, took him to court and won. The article presents Kuhn’s view as decidedly retrograde, telling readers that “At the heart [of the court case] was Ludtke’s fundamental right to pursue her profession as a woman, which otherwise granted men an unfair advantage. Kuhn’s argument was that his decision was necessary ‘to protect the image of baseball as a family sport’ and ‘preserve traditional notions of decency and propriety.’”

By the late 1970s, “traditional notions of decency and propriety,” under concerted attack for years, didn’t count for much in a liberated world.

If any men were made uncomfortable by the presence of women in their change rooms, their concerns were not even entertained. No women’s group or feminist advocate seems to have objected either. In the pre-trans 1970s, most women were unfazed by the prospect of being the lone woman amidst high-testosterone near-naked men, and feminist activists saw no disadvantage to women in minimizing the fact of sex difference.

The locker room triumph became a paradigm for the equality movement of the 1970s and ‘80s, as male bastions fell one by one. The idea that men might claim any space as their own came to seem, almost overnight, an ugly relic of bygone times, as states and cities in quick succession took steps to prohibit male-only businesses or clubs. The coup de grace came in 1987 when, in response to a lawsuit by the Rotary Club of California, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it was perfectly constitutional to ban sex-discrimination in business-oriented private clubs, making clear that women’s interests outweighed men’s.

Finding that the Rotary Club’s evidence “fails to demonstrate that admitting women will affect in any significant way the existing members’ ability to carry out [club] activities,” the Supreme Court judgement went further to clarify that “Even if the [Unruh] Act does work some slight infringement of members’ rights, that infringement is justified by the State’s compelling interests in eliminating discrimination against women and in assuring them equal access to public accommodations. The latter interest extends to the acquisition of leadership skills and business contacts.” By the late 1980s, “eliminating discrimination” had been broadened in law to mean equal access by women to anything positive men had made that women now wanted, including the networking opportunities and associations men had built over decades.

Shortly after the ruling, the New York Athletic Club, founded over a century earlier to offer athletic facilities as well as meeting places for men such as restaurants and lounges, was also forced to admit women.

As male-only spaces were being equalized, affirmative action and equity hiring initiatives saw women’s numbers swelling in formerly male-majority domains such as newsrooms, courthouses, legislatures, boardrooms, government offices, and university classrooms. By the 1980s, female university students were already at par with (and soon to surpass) their male colleagues , while female lawyers, doctors, and business owners were flooding into once-majority male fields. The two decades demonstrated the relative ease with which women were establishing a dominant presence in a formerly man’s world.

It had been male because men had built it. In North America, men had, within living communal memory, hewn civilization out of the wilderness, building roads, bridges, mills, farms, centers of trade, industries, sewer lines, and the electrical grid; establishing law, a police force, a judiciary, a military, markets, hospitals, food processing plants, and centers of learning. They had invented labor-saving technologies and had built highly complex city-systems. They had done it because that’s what men do—not as an act of exclusion but because, as Roy Baumeister argues persuasively, “system-building and empire-building appeal to the male mind” (Is There Anything Good About Men? p. 155). Women had been laboring too, of course, bringing children into the world and managing household economies. Until the late nineteenth century and later—and only then in urban centers—it had hardly been possible for women to work alongside men in significant numbers.

It’s not clear that men were under any moral obligation to admit women to the spaces they had made theirs—many men have never felt at home in feminine domestic spaces—and if men had wanted to, they could have resisted women’s call for equal access; for the most part, however, men welcomed and supported women’s professional and business advancement.

The women’s movement, however, not content with measurable gains, was unable to rest until every vestige of the old order had been destroyed. Feminists’ next step was to discover that workplaces were not always perfectly welcoming. Some women didn’t like their bosses or the men they worked with; some felt uncomfortable with men’s sense of humor or manners. With the help of policy-makers and legislators, feminists created an arsenal of rules designed to empower working women under the guise of protecting them from harassment and hostile environments.

But the legislation was always about more than that. The very style of work-life was forced to change under the new dispensation. In particular, every interaction between men and women, including even such minutia as eye contact, gestures, and compliments, was placed under the regulatory and oft-punitive regime of anti-harassment legislation, which Daphne Patai has chronicled as “the quixotic pursuit of a sanitized environment in which the beast of male sexuality [would] at long last be vanquished” (11). Any man who fell afoul of the (elastic and subjective) rules, or was merely claimed to have done so, could see his reputation and career destroyed.

Such policy and legislation changes—many of them undermining commitments to due process and the presumption of innocence—could never have been implemented were it not for the bedrock belief that male spaces were associated (as in “locker room talk”) with sexual menace, the degradation of women, and men’s corruption of one another. This belief is at least as old as the feminist movement itself, having galvanized such activists as radical suffragette Christabel Pankhurst, who called for “Votes for Women” and “Chastity for Men!” Women, of course—allegedly lacking power and the killer instinct—never needed to be monitored or restrained, never encouraged one another in bad behavior, and would never abuse the destructive license harassment legislation had given them.

It wasn’t surprising that even the Boy Scouts of America, once the byword of decency, modesty, and rectitude, could not be allowed to stand. The most famous feminist organization in the United States, the National Organization for Women (NOW), pulled out all the feminist stops in a 2017 press release that charged the Boy Scouts with failing in its duty to American children and championed the demand for admission of 15-year-old Sydney Ireland: “I cannot change my gender to fit the Boy Scouts’ standards,” Ireland alleged, “but the Boy Scouts can change their standards to include me.” Lest there be any doubt about the seriousness of their attack, NOW called on the federal government “to prohibit any federal support for the Boy Scouts until the organization ends its discriminatory ban against girls.” Naturally, NOW did not lobby the Girl Scouts to let boys in, with the result that there are now two scouting associations in the country, one that boasts of equal access, and one that touts the special advantages to girls of a female-only space.

Interviewed about whether the Girl Scouts of America had changed in the wake of the opening of Boy Scouts, the CEO of the Girl Scouts expressed her conviction that “There are very few opportunities for girls to be in a single-gender space where they can rely on one another, build relationships with one another, be themselves, not have to compete for space, not have to show off in any kind of different way.” It is difficult to avoid incredulity that so few in our culture seem able to understand that single-sex spaces might be just as necessary for boys or even more necessary in a feminized culture that actively dislikes boys and seeks to make them subordinate to their female peers.

***

Many men, happy in the company of women and fortunate (at least for the time being) in their circumstances, have adjusted to the feminist new normal. For other men, however, the erosion of male space has left them uneasy and justifiably angry. Now, after years of forced accommodation to feminine norms and requirements, men are expected to rise up in defense of female spaces—allegedly against a renewed patriarchy. The gall of the women who demand this male support, regardless of the willingness of many men to give it, seems boundless.

For more articles like this see Janice Fiamengo’s Substack