I’ve been a so-called coward and a so-called hero and there’s not the thickness of a sheet of paper between them. Maybe cowards and heroes are just ordinary men who, for a split second, do something out of the ordinary. That’s all.

Joseph Conrad- Lord Jim

My brother Stu and I have always been fascinated and obsessed by the concept of courage. On returning from a trip to South Africa, Stu informed me he had a special gift for me which was delayed due to it being placed in quarantine in Perth. Was it a wild beast? No. It was a Zulu shield hand crafted by a Zulu and made from raw cowhide. It hangs on my wall to this day-a glorious symbol of so much. Courage, brotherhood, childhood memories and passion.

From a very young age, perhaps after our dad had taken us to the Rivoli Theatre in Camberwell to see the classic film, Zulu, we were forever after entranced by stories of brave warriors and great battles.

We were not unique in this passion. Most young boys were preoccupied with fighting bloody wars in the backyards and streets of our neighbourhood. We used sticks for guns until we were given toy guns at Christmas. It was wonderful fun to pretend to be shot and fall in the most dramatic and spectacular fashion.

We were each given a box of toy soldiers when quite young one Christmas. The two armies of the American revolution. Stu received the box of redcoats and I the American blue coats.

Oh, the joy those soldiers brought into our lives. They were quality toys soldiers too. Each plastic warrior had a head that swiveled, a rifle or sword which could be removed from their hands and removable hats. Each soldier had clearly visible features on their face.

The battles in the loungeroom or hallway of our home were respectfully avoided by the rest of the family. They would tip toe around our troops as they stood in their lines, preparing to march into hellfire. Mum would leave our chosen battlefield room as the last to be vacuumed.

This passion for all things battle- related did not diminish as we grew. My dad noted that I in particular, loved to hear any stories of great deeds and heroics from the past and he relished the opportunity to share the many facts he knew with his besotted son.

Stu was more a man of action than me. He got involved in numerous fights as he went through his teenage years. I had a few scuffles and got punched up on a couple of occasions by a nemesis named Ross. But I preferred to lose myself in a good history book or novel while Stu was out partying and drinking.

Our bond remained during these years. We still talked about incidents of bravery we had witnessed or read about. It may have been a tale of a mate standing up to a group of thugs or the latest insight I had gained into what really took place at the Battle of Waterloo or during Hannibal’s brilliant crushing defeat of the Romans at Cannae.

We admired courage on the footy field, whether it be the bravery of fellow teammates in our local competition or the inspirational deeds of our heroes at our beloved Collingwood Football Club.

Courage was an underlying theme which connected so many of the passions we indulged.

Don’t misunderstand. I was the furthest thing from a bold, reckless boy you could imagine. I never rode a bike; I became anxious when serving as an altar boy and used to dread the weekly mass at which I had to serve. I was anxious when attending gymnastic classes, tennis lessons and secondary school. I lived in dread of the leather straps our Christian brothers kept on their person in case the need for a boy to receive six of the best arose.

When I was old enough to get my driver’s license, I was a mess on the day of my test. I scraped in and I still remember my hands were shaking so much I could barely sign the form they handed me to complete the process.

I was fascinated by courage. I never said I employed it on a regular basis. But this fascination demands some kind of examination as it has been an ever-present thread in the tapestry of my life.

The quote I used in the introduction to this piece certainly rings true. I think each one of us could recall a day where we acted with great courage and another where we failed to stand up when a situation demanded we do just that. We always have to live with the consequences.

I write this as a man and my entire focus will be on men.

There are countless women who have displayed the most stunning bravery throughout history. That is a given. But society does not expect or demand such behavior from women.

A woman who fails to show courage in a moment where it is required does not tarnish her reputation or status.

A woman who screams or cries in the face of danger is not mocked or denigrated.

A woman who fails to protect her husband is not reviled.

Men, whether they are consciously aware of it or not, live each day with the certain knowledge that if the proverbial shit were to hit the fan at a time when they happened to be in the vicinity, then action of some kind is the minimum requirement.

A savage, rabid bull terrier breaks free from its owner’s grasp and comes bounding toward the little girl in the park.

A group of loud, aggressive, intoxicated youths abuse your fiancé as you walk past them on a street corner.

A fire breaks out in a packed picture theatre.

A lone gunman walks into the local café and starts shooting.

A swimmer waves frantically about fifty metres from the shore- he is in trouble.

In every scenario, a man would feel an enormous pressure to do something to either protect or save the threatened individuals. The alternative for a man is almost more frightening than the dangerous scenario they are facing.

And let us make no mistake. I am a very empathetic and compassionate person, yet, whether it be right or wrong, I would most definitely judge a man who failed to respond and at least attempt to react to the imminent threat in any of these situations.

Perhaps not so quick to judge when a man is unarmed and faced with a rampaging gunman!

I cannot disentangle myself from the rest of my masculine brethren and pretend I would not feel some level of disdain for a man who failed to risk himself in the service of another-particularly if that other was a weak, vulnerable person.

It might be a feeling I try hard to ignore or push away, but it would be there.

I must remind myself that we cannot control how we feel in the immediate aftermath of any incident or confrontation.

When my son played football, I desperately hoped he would be a courageous footballer. Nothing made my body flood with pride more than when he risked his physical safety in order to win the football or help out a teammate. I can say that my son was an incredibly brave player.

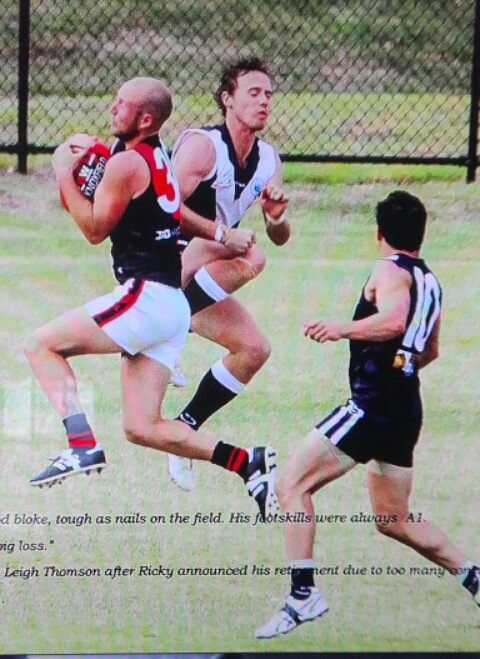

There is a photo I love which shows my courageous son running hard into an oncoming collision in order to mark (catch) the football. He didn’t flinch. The opponent coming in the other direction could have put him in hospital had he arrived a split second earlier. My son marked the ball, ran on and kicked a goal. I had tears in my eyes and goosebumps erupted all over my body.

Supporters called out their approval and recognition of his brave action.

There is text written over the photo of the words his coach spoke after Ricky announced his retirement due to his multiple head concussions. “Tough as nails” was how he described my son. Again, I felt that deep glow of pride.

Would I have loved my son any less if he had been a timid footballer? Absolutely not. Would I have felt ashamed if he had jumped out of the way whenever a physical confrontation loomed?

Yes.

I don’t think any dad would feel any differently. As Americans like to say:

“It is what it is.”

I would feel ashamed of my shame. But as I said, I cannot control my gut reaction to anything I experience, and I know it would have grieved me to think others thought my son was a soft footballer.

I have written about a moment of weakness in which I pulled out of a contest when I was a young man and how it devastated me when I realized my coach had not missed my shameful decision to avoid a fierce collision rather than get buried in the muddy turf.But there were also days when I played with great courage. That is why Conrad’s quote from Lord Jim resonates so deeply with me.

After one particular game which my dad had attended, he went home as soon as the final siren sounded so I didn’t see him until much later that same night. I was sitting on the loungeroom floor watching tv when he walked past me, reached down and ruffled my hair, saying:

“You’re a gutsy little fella!”

He then continued to walk on and left the loungeroom. That moment took all of five seconds. I am still talking about it forty years later, feeding off the nourishment and sustenance I absorbed knowing my dad was proud of me.

There is of course another kind of courage which is just as important and inspiring. Moral courage seems to be in rare supply these days. The willingness to take a stand against the mob. To swim against the tide. To speak unpalatable truths. To risk your livelihood in your quest to live with your conscience.

Dad made sure I was just as inspired by moral courage as I was by physical bravery.

The opposite of courage is not cowardice, it is conformity. Even a dead fish can go with the flow.

Courage matters.

The brilliant author and playwright, Oscar Wilde was sentenced to two years hard labor for the crime of sodomy in 1895. Wilde suffered terribly, for a man who was accustomed to the soft opulent life of a successful writer, the brutal regime in prison nearly killed him.

He wrote along letter, titled De Profundis during this time. It contains a passage which has always touched me deeply and has been a source of inspiration and a constant reminder to always stand by my friends, especially when they have been shunned, shamed or branded as being less than desirable company due to a change in fortune or circumstances.

When Wilde was condemned the general public reviled him. Whenever he was dragged out into the public spotlight, as occurred when being transported via a train at Clapham Junction Station, handcuffed to a policeman, the crowd recognized him and

“started shouting and spitting on him.”

On another occasion when being led from court in handcuffs through a large angry mob he recalled:

When I was brought down from my prison to the Court of Bankruptcy, between two policemen, – waited in the long dreary corridor that, before the whole crowd, whom an action so sweet and simple hushed into silence, he might gravely raise his hat to me, as, handcuffed and with bowed head, I passed him by. Men have gone to heaven for smaller things than that.

Wilde’s dear friend, Robbie Ross, had stepped out from the crowd and raised his hat to his manacled friend as a show of love, loyalty and respect.

What impact did this small, yet courageous and powerful gesture have upon Wilde?

It was in this spirit, and with this mode of love, that the saints knelt down to wash the feet of the poor, or stooped to kiss the leper on the cheek. I have never said one single word to him about what he did. I do not know to the present moment whether he is aware that I was even conscious of his action. It is not a thing for which one can render formal thanks in formal words. I store it in the treasure-house of my heart. I keep it there as a secret debt that I am glad to think I can never possibly repay. It is embalmed and kept sweet by the myrrh and cassia of many tears. When wisdom has been profitless to me, philosophy barren, and the proverbs and phrases of those who have sought to give me consolation as dust and ashes in my mouth, the memory of that little, lovely, silent act of love has unsealed for me all the wells of pity: made the desert blossom like a rose, and brought me out of the bitterness of lonely exile into harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.

Moral courage changes lives just as surely as physical courage can save them.

My brother, Stu died early last year. That Conrad quote at the start of my article was used on the front cover of his funeral booklet at his request. No-I am not going to regale you with a story of his brave fight with cancer. He was no braver and no less fearful than most people who face this disease.

But Stu had a raw physical courage which I do want to acknowledge and memorialize. We used to work out in his garage simply to keep in shape as the years began to take their toll. We loved to compete and “trash talk” each other as we did it.

One evening Stu announced he was going to fight in the Masters Games that were to take place in a few months’ time. Stu had boxed for a short time as a young man but work commitments had meant he couldn’t devote himself to the sport in the way he wanted to. At the age of 55 he was going to remedy the sense that he had unfinished business.

I watched him train relentlessly. The sparring sessions with the Australian Middleweight champion, Tej Singh, were more brutal than anything he faced in the Master’s tournament.

I saw him before his fights. I saw the fear in his eyes and felt sick at the thought of having to endure those long hours before stepping into a ring to fight a man you do not know in front of a crowd of mostly strangers. That was when I felt most in awe of his courage. He looked sick and distracted. But he walked to the ring and he fought and he won.

On the day of his fight to decide the Victorian Masters Champion, my wife and I were watching him as he sat and waited to be called to the centre ring. He looked tired, washed out and nervous. Only now can we look back knowing he was already fighting with a cancer ridden body.

Well, Stu won the state title. He wanted to go on and fight in the Nationals but cancer put an end to that.

You’d be happy to know that Stu was an avid anti-feminist and loved nothing more than to get on Facebook and fight the good fight with them. He was every bit as passionate as me when it came to defending men and demanding they be given the same compassion and consideration as women. Like any man brave or silly enough to speak up on behalf of men, he won himself plenty of enemies in that fetid swamp.

A week before he died, Stu asked me to include a clip from Zulu in his funeral service. I thought I had misheard him.

“How exactly will I manage that?” I asked him.

“You’ll find a way. Tell them I want it because it’s all about courage in the face of overwhelming odds. Tell them to crank up the volume. Everyone will get goosebumps.”

Well-I found a way and that clip was shown on a giant screen on the stage at the Karralyka theatre.

I miss my beautiful, crazy, tough brother. Did I tell you he cried when he watched old musicals like Carousel and Brigadoon? He was a talented singer and musician and wrote and sang a song he dedicated to me after I lost my leg and we could no longer run together. He was so much more than a macho man. His three adoring daughters and wife would attest to that.

So, I continue to read military history books. I read some passages over and over again. I am currently reading an incredible book on the Anglo/Zulu War of 1879. There are journal entries by soldiers who describe the hand to hand combat in details rarely used in the Victorian era of stiff upper lips and the silent treatment.

A dear American friend of mine who was conscientious objector during the Vietnam War asked me in a despairing tone one night:

“Why are so many of your heroes military men?”

I knew why.

I want to observe men in the moments where death is a breath or heartbeat away. What does friendship mean to them in that moment? What do the values they claim to live by and cherish amount to in that crucible?

And of course, the biggest question is for myself.

What would I do? How would I behave? Could I remain true to all I hold dear when I am safely tucked into my bed or enjoying the company of dear friends?

I felt tears well in my eyes as I read a passage from my book on the Zulu Wars.

Twenty-five thousand Zulus swarmed over a camp of fifteen hundred British soldiers and native contingents at Isandlwana. When the end was near, small groups of red coats clustered together in order to better defend their position but also for the comfort of standing shoulder to shoulder with their mates.

One recalls his officer, a young man himself in his twenties, calmly guiding them:

“Keep together boys, Keep steady.”

A brutal death is moments away, yet the man faces his annihilation with grace and composure and calms those who face the same brutal end. How can I not be drawn to such literature?

The courage of the Zulus was no less astonishing.

One man who wrote of his experiences in the heat of battle with the Zulus at Isandlwana was honest enough to say that as he rode for his life, hotly pursued by Zulus, a wounded man, Band Sergeant Gamble, pleaded with him to pull him up onto his horse.

He said:

“For God’s sake give us a lift!’

Brickhill’s response:

“My dear fellow, it’s a case of life and death with me!”

Brickhill rode on and survived. His “dear fellow” was stabbed to death moments after he deserted him.

The author remarked that this moment troubled Brickhill’s conscience for years to come.

Only minutes later another man on horseback. Private Samuel Wassall of the 80th regiment faced the same dilemma. With all of his instincts telling him to keep fording the river in order to reach relative safety on the far shore, he turned his horse, went back and retrieved the desperate man, a private by the name of Westwood, who had called for help. He saved his life and both men lived to tell the tale. As he said in his own words:

“There was a terrible temptation to go ahead and just save oneself. But I turned my horse round to the Zulu bank, got him there, (his horse) dismounted, tied him up to a tree (and I never tied him more swiftly). Then I struggled out to Westwood, got hold of him and struggled back to the horse with him…..I plunged into the torrent and as I did so the Zulus rushed up to the bank and let drive with their firearms and spears. Mercifully, I escaped them all, and with a thankful heart, urged my gallant horse up the steep bank on the Natal side.

Which man am I?

Both of them, of course.

Courage.

What an unbelievably complex concept. Yet it is an issue that every man must wrestle with his whole life.

In memory of my beloved brother, Stuie.

Read the quotes below. Each one of them carries the ring of truth yet many are in direct contradiction of each other. Which one resonates best for you?

Any coward can fight a battle when he’s sure of winning; but give me the man who has the pluck to fight when he’s sure of losing.

George Eliot

Courage is nine-tenths context. What is courageous in one setting can be foolhardy in another and even cowardly in a third.

Joseph Epstein

To a coward, courage always looks like stupidity.

Bill Maher

Some have been thought brave because they were afraid to run away.

Thomas Fuller

A timid person is frightened before a danger, a coward during the time, and a courageous person afterward.

Jean Paul

The difference between a hero and a coward is one step sideways.

Gene Hackman

That man is not truly brave who is afraid either to seem or to be, when it suits him, a coward.

Edgar Allan Poe

Many would be cowards if they had courage enough.

Thomas Fuller

Alas, nothing reveals man the way war does. Nothing so accentuates in him the beauty and ugliness, the intelligence and foolishness, the brutishness and humanity, the courage and cowardice, the enigma.

Oriana Fallaci

Fear is far more painful to cowardice than death to true courage.

Philip Sidney

The opposite of courage in our society is not cowardice, it is conformity

Rollo May

Courage is often lack of insight, whereas cowardice in many cases is based on good information.

Peter Ustinov