Long before CGI, humans being menaced by giant creatures they had previously dwarfed had great cinematic allure. In particular, the 1950’s were rife with science fiction films involving tiny creatures grown gigantic. To wit:

YEAR CREATURE(S) TITLE

1954 Ant Them!

1956 Tarantula Tarantula

1957 Scorpion The Black Scorpion

1957 Grasshopper Beginning of the End

1957 Praying mantis The Deadly Mantis

1958 Spider Earth vs. the Spider

1958 Wasp Monster From Green Hell

1959 Leech Attack of the Giant Leeches

Since human disgust with creepy-crawlies appears to be instinctive (consider the Insect Fear Film Festival held every year since 1984 on the campus of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), it is only logical that giant creepy-crawlies would send the fear factor into overdrive, thus assuring a B movie bonanza.

Obviously, the aforementioned movies are hardly the stuff of Oscar nominations. But one such movie has achieved a rare status – and it has great implications for the manosphere, even though it came out long before anyone ever heard of the manosphere. In fact, it is a pop cultural touchstone from that dreaded decade of patriarchy – the 1950’s!

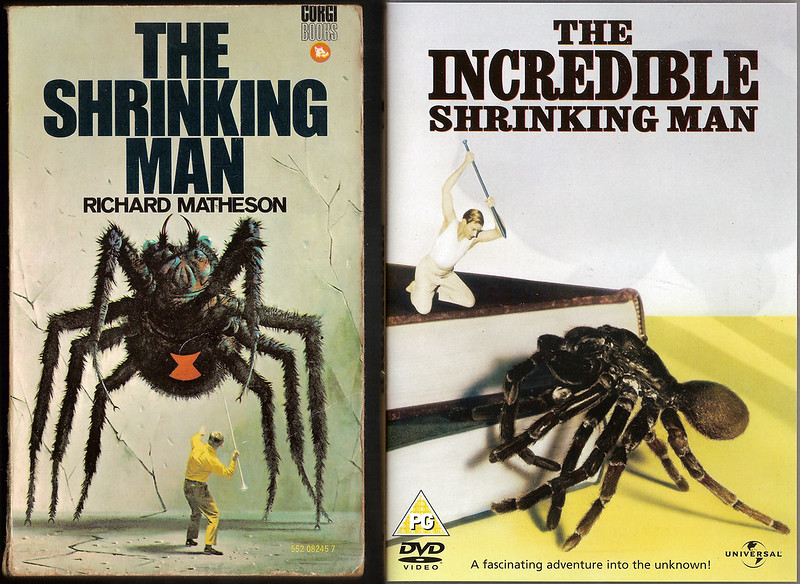

Perhaps the best known scene in The Incredible Shrinking Man is a battle between the shrunken protagonist and a normal size tarantula; in effect, a giant tarantula. Given its title, the film would certainly look fitting on the marquee of a drive-in theater in 1957, the year of its release. In fact, it could have been offered up in a double feature with a number of other lurid 1957 titles (e.g., I Was a Teenage Werewolf, Attack of the Crab Monsters, The Amazing Colossal Man, and, believe it or not, a proto-female empowerment tale, The Saga of the Viking Women and Their Voyage to the Waters of the Great Sea Serpent).

Despite its title, The Incredible Shrinking Man went from B-movie stigma to A-list status. In 2009 it was inducted into the National Film Registry, a repository for “culturally, historically, or aesthetically” distinguished movies.

Based on “The Shrinking Man,” a 1956 story idea by Richard Matheson (who also wrote a novel based on the screenplay, which he co-authored), the film has a deceptively simple concept: Scott Carey (Grant Williams), a normal-sized adult male starts growing smaller. While shrinkage is a longstanding male fear, it is usually restricted to the genitalia. The protagonist of this film grows smaller but his body remains in proportion.

Shrinking humans was not an entirely new cinematic concept (e.g., The Bride of Frankenstein in 1935 and Dr. Cyclops in 1940). After 1957, the shrinking of humans continued in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989) and Downsizing (2017). But once the subjects had shrunk to a certain size, the process stopped. Not so with the 1957 shrinking man. Scott Carey continues shrinking away to…microbe size? Virus size? Molecule size? Atom size? Subatomic particle size?

While atomic radiation was the usual explanation offered for gross size disparities in 50’s films, Shrinking Man wisely bypasses this cliché. Rather, Scott Carey starts to get smaller after an encounter with a mysterious fogbank and it is determined that his molecular structure has been rearranged. Actually, the cause really isn’t important. It’s just a springboard for the plot of the movie, filled with challenges and perils that Scott must face as he grows smaller – not to mention ample opportunities for trick photography.

Scott first notices that his clothing has become baggy – an experience any dieter might welcome – but Scott hasn’t been trying to lose weight. He shrinks to the size of a midget, then to the size of a dollhouse occupant, and finally down to the size of a fly, at which point he encounters the predatory tarantula. (Fun fact: Director Jack Arnold had directed Tarantula the year before, so he is likely the only director in cinema history with two movies featuring a giant tarantula!)

Much like The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, another 50’s science fiction classic that was inducted into the National Film Registry, the film invites a number of interpretations, and those interpretations may change depending on the era when the viewer sees the film. Consequently, the film has a resonance today that it didn’t have when it was first released.

In 1957 contemporaneous interpretations might have been the loss of autonomy in a mass society. Possibly a “shrinking” of rights and freedoms in a society growing more and more oppressive, whether capitalist, fascist, or communist. 1957 was also the year of Sputnik, so the beginning of space exploration might have drawn attention to man’s undeniably puny presence in the universe. Then as now, it could be interpreted as a man wasting away while battling a disease with no hope for a cure. One topic that was not hot back then was feminism.

In 1957 Betty Friedan began working on a project that resulted in The Feminine Mystique, eventually published in 1963. So when Shrinking Man arrived on motion picture screens, the second wave of feminism was gestating, but the pregnancy hadn’t started to show. It was still OK for a man to be a man, however you interpret that. It may have been a nod to the sacrifices made by World War II vets, or perhaps a realization that prosecuting the cold war necessitated the maintenance of traditional masculinity. At any rate, men and masculinity, in reality or as concepts, were not under siege.

Of course, that started to change during the 1960’s. Then it became possible to interpret the shrinking man of the movie as a loss of status vis-à-vis his wife (who becomes relatively larger simply by remaining the same size). Scott’s presence in his household shrinks along with his body – as do his place in society and in the world.

Today, as manhood is mocked, as testosterone levels plummet, as calls for equity grow louder and louder, The Incredible Shrinking Man achieves more and more significance. It’s not too much of a stretch to add race to the mixture, since Scott, though portrayed as an everyman, is undeniably WASPy.

Oddly enough, this science fiction movie about a man wasting away to nothing could be a nod to existentialism. Sartre’s seminal work, Being and Nothingness, could almost be a subtitle for The Incredible Shrinking Man. So could No Exit, a play by the same author. It is entirely possible that Richard Matheson (born in 1926) was familiar with the aforementioned works, as they were written in the early 1940’s.

With no hope offered for stopping or reversing the shrinking, the film could have ended on a decidedly downbeat note. Normally, when offered a sympathetic protagonist, viewers expect to see him triumph. Instead, we are given a soliloquy worthy of Hamlet:

I was continuing to shrink, to become…what? The infinitesimal? What was I? Still a human being? … So close, the infinitesimal and the infinite. But suddenly I knew they were really the two ends of the same concept. The unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet, like the closing of a gigantic circle. I looked up, as if somehow I would grasp the heavens, the universe, worlds beyond number. God’s silver tapestry spread across the night. And in that moment I knew the answer to the riddle of the infinite. I had thought in terms of Man’s own limited dimension. I had presumed upon Nature. That existence begins and ends is Man’s conception, not Nature’s. And I felt my body dwindling, melting, becoming nothing. My fears melted away and in their place came acceptance. All this vast majesty of creation, it had to mean something. And then I meant something too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something too. To God, there is no zero. I still exist.

Well, you can imagine moviegoers at drive-ins scratching their heads in confusion after returning the in-car speaker to its post and driving out of the theater. The usual mainstream movie ends with a restoration of order, no matter how much chaos is portrayed in the film.

A conventional ending for Shrinking Man would have restored Scott to his original size (indeed, such an ending was under serious consideration) yet with having changed for the better after surviving his ordeal. The ending as it stands is a curious one. Scott Carey has survived all the ordeals he faced, but so what? His quasi-religious awakening may offer solace but it won’t stop the process. So what’s the meaning of the ending for men today?

Let’s assume that men are not going to be restored to their rightful place in society any more than the Scott is going to stop shrinking and grow larger. Do men have to accept their situation as inevitable, as Scott does in the final scene? Scott no longer has a place in society but that doesn’t mean his life is meaningless. It’s not that Scott goes MGTOW – he has no choice. Given the reality of his situation, he might as well commit suicide by tarantula. Yet his will to live has not shrunk. In fact, the smaller he gets, the more gets in touch with his primal instincts, the drive to live, the drive to triumph over adversity. Arguably, he is more alive than he was in his “normal” existence.

So the lesson for men is this: If you don’t have a place at the table in society, you still have one at the table of life. And your table setting is secure no matter how big or small you are. So even if you’ve been dismissed as a misogynistic patriarchal troglodyte – even if you are unvaxxed! – you are still alive.

If you think these are dark days for men, perhaps you can take heart from The Incredible Shrinking Man. No matter what the academics, the mass media, and the government say, as long as you draw breath, you still count for something.