Doubtful Sound in New Zealand is one of those places you should see before you die. The scenery is enough to eclipse any of my paltry attempts to describe it, but I can try to tell you what I saw; scattered, small emerald peaks rising out of placid, reflecting water the color of tea. Still larger rocky summits, capped in rugged ice, reaching up to meet a sky of blue-gray steel. They stood like ancient sentinels in a timeless place.

Getting there is a day long event, no matter where you start. It involves a boat ride across the impressive expanse of Lake Manapouri, then boarding a tour bus for an hour long 22 kilometer drive across the Wilmot Pass on a gravel road, ultimately rolling down a long, winding, dizzying grade to the waters edge.

It is like a trip backward through geologic history, and would seem to be the most unlikely place on earth to stumble on an example of sexual politics gone awry, but that is precisely what happened.

The tour bus I was on took a slight detour en route to the boat waiting for us on the sound. The driver/tour guide spoke in a friendly, informative manner as he steered the bus into a 2 kilometer long tunnel that had been blasted and scraped directly through the solid granite of the Fiordland mountains.

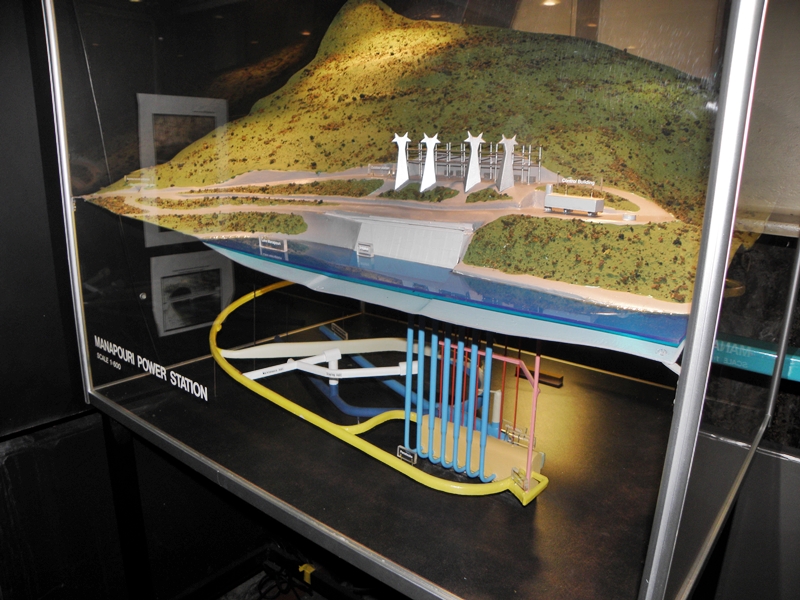

At the end of that tunnel we filed off the bus to take a short tour of the Manapouri Power Station. It would initially seem to be a yawner of a side trip, but I was quickly educated otherwise. The Manapouri Power Station is an engineering and technological marvel, arguably one of the greatest collective accomplishments in New Zealand history.

It operates by channeling lake water past turbines buried deep in the mountainside and then sending it down the 10 kilometer long tailrace tunnel, excavated from the same, almost impervious granite. It shot down to the sound below and out to the Tasman Sea.

And when I learned a little more of the history of the project, it got even more interesting.

Especially the way I learned about it.

I was informed by the power station tour guide, not my driver/guide but a power station employee, that it took sixteen hundred “workers” two years to excavate that tunnel. And that in the process, 16 “workers” were killed.

It was a spiel I was used to. When men die on the job, they are not men. They are “workers.” Sometimes they’re “firefighters,” “soldiers,” and other professional labels designed to distract us from the idea that they are human beings. Sometimes, they are even reduced to something as generic as “personnel.”

Anything but men.

And of course I listened to this with the certainty that if by any chance any of those “workers” happened to be female, I would have heard the now obligatory woman inclusion. The tour guide would have to work from an amended script, telling us that 16 “workers” died, including one woman. Or something like that.

And that is par for the course. A regular reminder that men die on the job in anonymity while women pass in the limelight, showered in accolades for posterity. It is something I don’t take to heart so much any more. I knew who built that power station; who conceived it, planned it, sweated and bled for it, even if the world obscures their identity with generic labels.

Hell, I didn’t even mind that the tour guide, the power station employee with the gender neutral script, was, in fact, a woman. Along with the rest of the world, I suppose that I’ve grown accustomed to seeing them move into good paying jobs after the dying is done.

Doesn’t mean a thing anymore. Just more postmodern bullshit in a world where 93% of all workplace deaths are still men.

But what got to me, what made my skin crawl and turn crimson was on the wall behind me; a backlit testimonial hanging on the wall above the row of exciters in the machine hall, informing us that when the men who dug that place out weren’t working, or dying, they were drinking themselves into oblivion and engaging with women of ill repute. Carousers to the last man, they were. It’s a wonder they got anything done.

There I was, standing above the plant’s machine hall, which was housed in a space carved out of a million metric tons of solid rock, listening to a female plant employee in a pink hard hat tell me about the “workers” who died building her place of employment; all while the wall behind me cast the men who did it like a bunch of drunks and derelicts.

I wanted to scream.

They said that somewhere in the plant was a plaque that bore the names of all the “workers” that died there, but that it was not in an area for public viewing.

Small wonder.

But I did, by chance, (and I mean literally by chance) stumble on a plaque outside the plant, at the very summit that led down to the sound after we left the power station. We stopped for the chance to take a photo from the top. At that time I noticed a small cutaway into the side of the mountain. It was dark and the sides of it were overgrown with local fauna.

But I did, by chance, (and I mean literally by chance) stumble on a plaque outside the plant, at the very summit that led down to the sound after we left the power station. We stopped for the chance to take a photo from the top. At that time I noticed a small cutaway into the side of the mountain. It was dark and the sides of it were overgrown with local fauna.

The tour guide didn’t say a word about it. I don’t think he even knew it was there. I just happened to go in and look while others were snapping pics of the sound from above.

I read the words and the end several times. I tried to imagine that kind of sentiment, “He loved his fellow men,” fitting with the mindless, alcoholic thugs they tried to tell me built that place.

And I wondered how many other “workers” who perished were such men as Terrence M.J. Smith. Men who loved, and who were loved and needed by others. Men who were cut short, first from their life blood in the name of a greater good, and then from their legacy, in the name of a great and ignoble lie.

The Manapouri Power Station