Scholarly books such as Howard Chudacoff’s Age Of The Bachelor, or J. McCurdy’s Citizen Bachelors have traced the historical rise of bachelor movements, which tend to occur when a given society sufficiently devalues men while saddling them with unreasonable demands of service to wives and the State. When societies treat males more favourably, then bachelor movements organically decline. The following paper by Japanese philosopher Masahiro Morioka (published at A Voice for Men in 2014) describes this trend playing out currently in Japan. – PW

* * *

A Phenomenological Study of “Herbivore Men”

1. Birth of the Term “Herbivore Men”

From 2008 to 2009, “herbivore men (sôshoku danshi or sôshoku-kei danshi in Japanese)” became a trendy, widely used term in Japanese. It flourished in all sorts of media, including TV, the Internet, newspapers and magazines, and could even occasionally be heard in everyday conversation. As it became more popular its original meaning was diversified, and people began to use it with a variety of different nuances. In December of 2009 it made the top ten list of nominees for the “Buzzword of the Year” contest sponsored by U-CAN. By 2010 it had become a standard noun, and right now, in 2011, people do not seem particularly interested in it. Buzzwords have a short lifespan, so there is a high probability that it will soon fall out of use. The fact remains, however, that the appearance of this term has radically changed the way people look at young men. It can perhaps even be described as an epochal event in the history of the male gender in Japan.

The term “herbivore men” became popular because of the existence within Japanese society of actual “men” to whom it applied. People had already picked up on the fact that young men who seemed to have lost their “manliness” or become “feminized” were increasing in number. Signs of this trend had existed from around the time highly fashion-conscious young men who dyed their hair light brown, wore designer rings, and pierced their ears started appearing at the end of the 20th century. At the time I had just transferred to Osaka Prefectural University, and I remember being surprised when I looked down from the podium to see nearly all of the first-year students, both male and female, had dyed their hair brown. Looking more closely, I saw that some male students had pierced their ears. Compared with the situation now, however, this scene seems quite nostalgic; on today’s campuses there are male students who dye their hair blonde and wear long skirts. Just the other day, for example, one of the young men who came to ask me a question after my lecture had fastened his loose black bangs with a big red hairpin like a schoolgirl. It was at the start of the 21st century that people began to sense that this type of young man, a man who is just as sensitive to fashion as a woman, is not noticeably muscular, and seems in some way to have a reduced capacity for violence, had increased in number.

Aya Kanno’s Otomen is a manga that has adroitly picked up on the atmosphere of this era. An ongoing serial that has been running in the magazine Bessatsu Hana to Yume since 2006, its protagonist is a young man who is outwardly athletic and manly but inwardly has the love of cute things and sensibility of a young girl. “Otomen” is a made-up word combining “Otome [young girl]” and the English word “men.” It is a manga that has taken up the gender confusion that has arisen among men as its theme, and it has been very well-received. 2006 was also the year that the term “herbivore men” first appeared. Writer Maki Fukasawa published an article entitled “Herbivore Men” in an online magazine called U35 Danshi Mâketingu Zukan [U35 Men Marketing – An Illustrated Guide]. In this essay she points out that the number of “herbivore men,” young men who, while not “unattractive,” are impassive regarding desires of the “flesh” and not “assertive” when it comes to love and sex, are increasing in the young generation. She mentions that even when these men spend the night with a young woman they may sleep together in the same room and then return home without having engaged in any sexual activity.

To older generations, the existence of such men is beyond comprehension. From the perspective of older people, whose “common sense” says that if you are a man then you should pounce on a woman whenever you have the chance, young men who do not belong in the category of “men” at all are increasing in number. Fukasawa also notes that since “herbivore men” are not unattractive they often have considerable romantic and sexual experience. The defining characteristic of herbivore men, however, is that they are not assertive or proactive in these areas. I will save my own comments on this point for later. In any case, the term “herbivore men” was coined in 2006. The word “herbivore” was taken from the phrase “herbivore animals,” and can be seen as having the connotation of a man who does not hunt women like a “carnivore” and is thus “safe” from a woman’s perspective.

“Herbivore men,” this new term proposed by Fukasawa in 2006, did not, however, take hold in people’s consciousness at the time. There was in fact almost no public response to it. It was not until 2008 that “herbivore men” suddenly gained widespread recognition. The May issue of the magazine non-no included a special feature entitled “Deai ‘shigatsu kakumei’ ni shôriseyo! Danshi no ‘sôshokuka’ de mote kijun ga kawatta!”[Triumph in dating’s “April revolution”! The standards of attractiveness have changed with the “herbivorization” of men!]. With the publication of this special feature in a popular magazine, knowledge of the term “herbivore men” crossed over into the general population. As the basic character of the majority of later statements on this phenomenon can be found within its pages, if you want to study Japanese herbivore men you must begin by closely examining this magazine feature.

Until the appearance of this special feature, the paradigm for Japanese women’s magazine articles on love and romance had been learning how to become “women who are loved” by men. They proclaimed that in order to become a woman who is loved, a woman must wear cute and sexy clothing to arouse male interest, skillfully endear themselves to men, appeal to male protective instincts, and employ techniques to cause the man she is targeting to come after her. The idea that men are looking to go after women whenever there is an opening presumably existed as an assumption underlying all of these undertakings, but this special feature claimed that this assumption had already begun to fall apart. Up until that time a man could be expected to automatically pursue a woman if she gave him an opening, but now the herbivorization of young men had begun, and, since they were no longer aggressive in matters of love and sex, a state of affairs in which they would not pursue her no matter how many openings she gave them had begun to arise.

This special feature accurately picked up on this change in circumstances, and offered instruction to its young female readership on how to catch these young men who had become herbivores. Let us examine its content. To begin with, the advantages and disadvantages of becoming romantically involved with herbivore men are listed as follows. The advantages are (1) herbivore men place a low priority on sex and thus will not use a woman for her body, (2) they are interested in the human qualities of a woman such as how pleasant and interesting she is, and (3) when it comes to romantic relationships they desire stability. The disadvantages are (1) romantic relationships develop slowly, (2) the standards they use when choosing a female partner are difficult to understand, and (3) you cannot expect a dramatic, passionate romance. As is evident from this list, this is quite far from the image of men as being assertive in matters of love and sex (soon to be dubbed “carnivore men”) that had long been assumed by women’s magazines.

As a result, this special feature proposed three requirements for becoming involved with herbivore men: (1) Herbivore men lack assertiveness, so the woman must take the lead in romance; (2) excessive scheming and romantic techniques are off limits, and should be replaced with more easily understood displays of affection; (3) herbivore men like women of substance, so women must elevate their human qualities.

Looking back on it now, the analysis conducted in this magazine feature seems quite incisive. In the second book I mention later in this article I interviewed actual herbivore men, and in many respects their assertions matched those in the magazine. Fukusawa, the woman who had first posited the existence of herbivore men, was also involved in this special feature. I suspect that Fukusawa and the female staff of the magazine, while brainstorming with each other, analyzed the lifestyle of the herbivore men around them and in the process brought into relief the outline of this type of man. After “herbivore men” became a mainstream term, I myself was interviewed by many women’s magazines and participated in the creation of content they published. In most of these cases, I experienced a process in which articles were written through a casual exchange of ideas between female editors, female writers, and external sources such as myself. Based on my impression at the time, I suspect that these women in their thirties working at the magazine may have put together the special feature mentioned above based on their own intuition and discussion of personal experiences. At a stage when mass media had not yet reported on “herbivore men,” women’s fashion magazines were already using this term extensively. As of the winter of 2008, the prototypical image of herbivore men had been formed primarily by magazines aimed at female readers.

2. Lessons in Love for Herbivore Men and What Came Afterwards

At the same time, the popularization of the term “herbivore men” also arose in conjunction with another source. This was a book of mine entitled Lessons in Love for Herbivore Men which was published in July of 2008. This was the first book to use the term “herbivore men” in its title, and following its publication it was reviewed in the Yomiuri Shimbun; this then led to its being discussed in various magazines and TV programs. There are those who have mistakenly assumed that the phrase “herbivore men” was coined in Lessons in Love for Herbivore Men, and this book was indeed written without any influence from the introduction of the term by Fukasawa or non-no. A book meant to provide guidance to kind-hearted young men who are late-bloomers when it comes to love, its manuscript was completed in 2007. When its title was being decided in April of 2008, the editor in charge suggested the term “herbivore-type men” in reference to the non-no special feature. I was not familiar with the phrase at the time. Rather than use the exact wording (“herbivore men”) that had appeared in the magazine, the editor decided in this case to add the word “type” (“herbivore-type men”). At the time it did not seem particularly significant.

Since the editor’s suggestion was accepted and the title of the book became Lessons in Love for Herbivore-type Men, in the afterword I added my own definition of this term. Although “herbivore-type men” appears in its title, this phrase appears only once in the book, and then only in the afterword. In the main body of the text the expression “kind and gentle men” is used exclusively to refer to these men who struggle with romance. For me, the issue of “herbivore-type men” was not a matter of fashion and external appearance but rather of internal thoughts and feelings. (Since then Fukusawa has stuck with “herbivore men” and I have continued to use “herbivore-type men” when writing in Japanese, but as the former term has become much more widely used in English this distinction will not be made in translating either my book titles or references to the concept itself in the remainder of this text).

It was also the editor’s idea to have popular young manga artist Inio Asano draw an illustration for the book’s cover. Asano drew us a somehow shy looking, skinny young man wearing black-rimmed glasses and a loose-fitting shirt with horizontal stripes. This illustration would, in fact, end up largely determining the image of herbivore men going forward. When images of herbivore men appear in magazines and on television, they are always extremely slender young men wearing black-rimmed glasses and striped shirts. The young man in this illustration doesn’t seem at all fashionable, but many people have been given the impression that herbivore men are young men who look like this.

But considering the content of the book, this message can be seen as a bit misleading. My assertion, directed towards gentle young men who are late-bloomers when it comes to romance, is that in romantic relationships the most important thing is not your appearance but how you build connectedness on the basis of a kind and gentle heart. What I tried to explain was that while young men are inundated by male media, and thus often come to believe that in order to have a romantic relationship with a woman you have to be a virile, “macho” man, in fact this belief is mistaken; you can love a woman without being a “macho” man, and indeed there are many women who prefer a man to carefully build a relationship based on kindness.

Lessons in Love for Herbivore Men was thus written as a guide on how to break the spell of “manliness” and learn to love. The “herbivore man” referred to in its pages is a man whose heart and mind is ready to create a tender relationship with a woman, not a man who is outwardly fashionable and effeminate. The type of reader I had in mind is a young man, inexperienced in romance, who cannot assertively approach a woman because of his gentle nature. In this sense my image of “herbivore men” was the exact opposite of Fukusawa’s. Her image was that of a man who is popular with women and has considerable romantic and sexual experience, whereas for me this was not at all the case. From immediately before it came into common use, our understandings of the term “herbivore men” were completely opposite.

From 2008 to 2009 the phrase “herbivore men” was widely taken up by the mass media, and in the process its meaning was extended. For one thing, while both Fukusawa and I used it to refer to young men who are not assertive regarding sex and love, it came to be used in reference to a man’s external appearance. This meaning of a slender, bespectacled young man with a feminine fashion sense was added; “herbivore men” was used to describe young men who, as I mentioned at the start, pay as much attention to their appearance as women and make use of the same accessories (rings, earrings, hair dye, barrettes, oil-removal sheets, etc.) In addition, it also began to acquire a pejorative, “too sissy to be considered a real man” connotation. Older male commentators appearing on television began to express concern for the future of Japan’s economy, worrying that the progressive “herbivorization” of young men might eventually result in a complete lack of assertiveness not just in romance but in every other aspect of life as well. Several “mini-dramas” in which female celebrities or ordinary women ridiculed herbivore men were also broadcast. There were many scenes in which the script had women say things like “men who aren’t assertive really aren’t attractive, are they?” Various opinions on what to think about herbivore men as members of the opposite sex circulated in the media. The opinions of both women who liked herbivore men and women who did not appeared in articles published in women’s magazines. Looking at the responses I received from female readers of my book, there were a surprisingly large number who held a positive opinion of herbivore men. Opinions commonly expressed by these women include a dislike for men who are looking to have sex right away, fear of men who are too pushy, a preference for letting romance progress slowly, and the belief that herbivore men are less likely to engage in domestic violence.

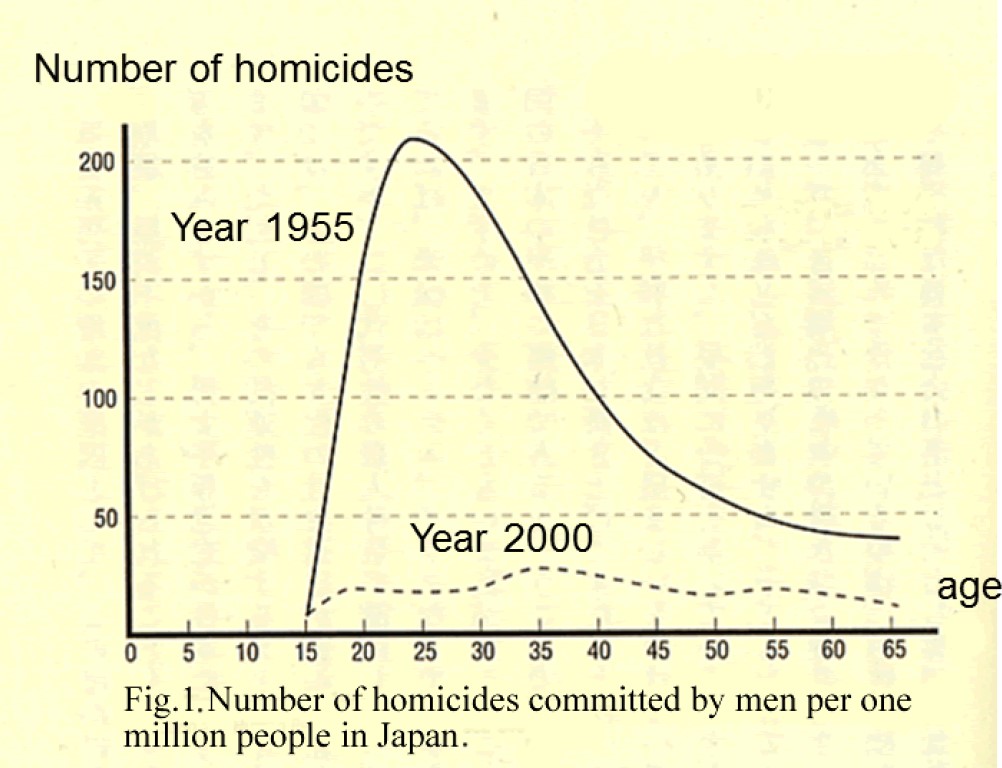

Having seen the meaning of “herbivore men” expanded and confused in this way, in 2009 I wrote Herbivore Men will Bring your Last Love and redefined this concept. I emphasized that for me “herbivore” refers not to a man’s external appearance but to his internal thoughts and feelings. I then offered the following definition: “Herbivore men are kind and gentle men who, without being bound by manliness, do not pursue romantic relationships voraciously and have no aptitude for being hurt or hurting others.” As a result, even a heavyset, broad-shouldered, muscle-bound man is a “herbivore man” if he possesses these internal traits. And no matter how slender, effeminate, and fashionable a man is, without these internal characteristics he cannot be said to be “herbivore.”

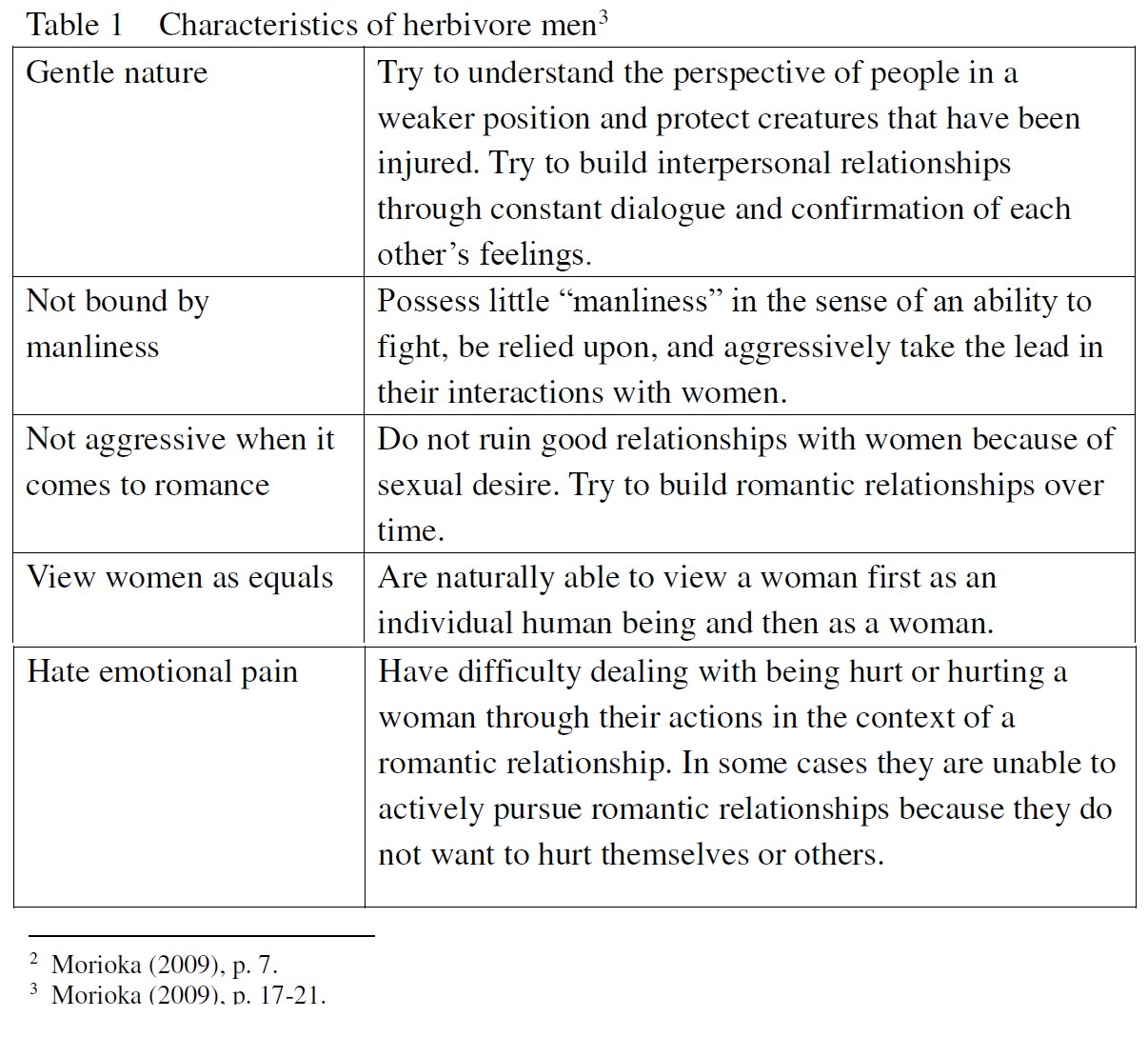

Obviously, however, men cannot be divided into only “herbivore” and “carnivore” types. For example, regarding romantic relationships, the distinction between “late bloomers” and “experienced lovers” is also important. It also seems better to distinguish between those who are herbivore deep down inside and those whose superficial behavior patterns are herbivore. Table 2 divides men into eight categories along these lines, with columns for each male romantic characteristic and methods for women to approach having a relationship with each type of man.

Of course, I acknowledge that this division of young men into eight categories is a bit forced, but I think it is a more useful framework than simply dividing them into herbivore and carnivore types.

I conducted extensive interviews with four actual herbivore young men, and by doing so was able to learn what sort of things they think about in considerable detail. There were several things that stood out as distinguishing characteristics. First, when it comes to love they do not put a very high priority on a woman’s appearance. Of course, like normal men they are attracted to cute and beautiful women, but they are fully aware that this is not the decisive factor in romantic passion. This applied to all four of the young men I interviewed. They also have difficulty with women who dress and present themselves in a particularly “feminine” fashion. As for why this is the case, one of them suggested that it was because when he is with a girl who demonstrates an exaggerated femininity he feels compelled to be very “manly” in response. Another wondered why it should be necessary to add a sexual relationship once he has built a good relationship with a woman. He also said it was “scary” when a woman tries to seduce him directly.

All of them said that when a woman suddenly touches them or comes on to them out of the blue they are bereft of feeling. The reason for this is that the situation develops without their being able to understand why they are being seduced. If a woman is going to come on to them, these men want her to first clearly state her affection for them in words and gradually engage in more and more intimate communication. They want to begin by becoming emotionally intimate; they want physical contact to arise naturally only after emotional communication has been carefully established. Within male culture, until now there has been the idea that a man’s role is to doggedly pursue a woman even if she puts up a bit of resistance; a woman may say no at first, but this is just a pose and eventually she will accept the man who pursues her. Herbivore men are acutely opposed to this kind of “manliness.”

Some of the young men I interviewed were “late bloomers” with little experience of being with a woman, but others had considerable romantic experience. It seemed that the herbivore men with a lot of experience, having lost their illusions about women, did not feel a strong need to engage in romantic relationships. Regarding marriage, too, there were those who expressed a strong desire to get married and those for whom it was not particularly important. In these areas there seems to be considerable diversity among herbivore men.

The existence of young men referred to as “herbivore” has been clearly demonstrated, but what percentage of young men in Japan fall into this category? No empirical surveys have been carried out to answer this question. Many simple questionnaires have been conducted by magazines and on the Internet, but they are of no scientific significance and little credence can thus be given to their results. To begin with, it is presumably meaningless to conduct questionnaires asking “Are you a herbivore man?” at a point in time when there is no consensus within society as a whole about to what exactly “herbivore man” refers. Among these surveys, however, perhaps the most interesting was an Internet questionnaire conducted by M1F1 Sôken in February of 2009 involving 1000 men aged twenty to thirty-four in the Greater Tokyo Area. 60.5% of these young men answered that they were herbivore men.

As I noted above, these responses are from a time when the meaning of “herbivore men” had not been defined and thus cannot be given much credence. The next response, however, is worth noting: 62.8% answered “I am not assertive in romantic relationships,” and 46.7% said “it is foolish to spend a lot of money to get close to (someone of) the opposite sex.” In other words, a majority of young men were already not assertive in romantic relationships and slightly less than half felt that spending a lot of money on romantic relationships was foolish. To some extent this can be seen as giving support to Fukusawa’s view that the number of men who are not assertive when it comes to love and sex is increasing.

So what do we see when we take an international perspective? The concept of herbivore men emerged only very recently in Japan, so we have no idea how many such young men exist in other countries. Here I would like to note that the international mass media has shown an interest in herbivore men. The People’s Republic of China’s Xinhua News Agency reported on herbivore men in Japan on its website as early as December 1st, 2008. Accompanying this article there was a large photograph of a slender, fashionable young man wearing black-rimmed glasses eating vegetables and bread.

The earliest reporting on this phenomenon in English was an article that appeared in the Japan Times on May 10th, 2009. On June 8th, 2009, CNN published an article entitled “Japan’s ‘herbivore men’ – less interested in sex, money,” and broadcast a report on television. On CNN’s website there was a photograph of a young, androgynous-looking Japanese man peering into a mirror and applying lip cream. Several other articles appeared in English-language newspapers, and reports also appeared in French and Spanish papers. If you search for “herbivore men” on the Internet you will get a large number of hits. A traditional-character Chinese translation of my Lessons in Love for Herbivore Men was published in Taiwan in 2010, and a simplified-character Chinese translation was published in the People’s Republic of China’s mainland in the same year. If the concept of herbivore men spreads to other countries in the future it will become possible to conduct international comparisons concerning this phenomenon.

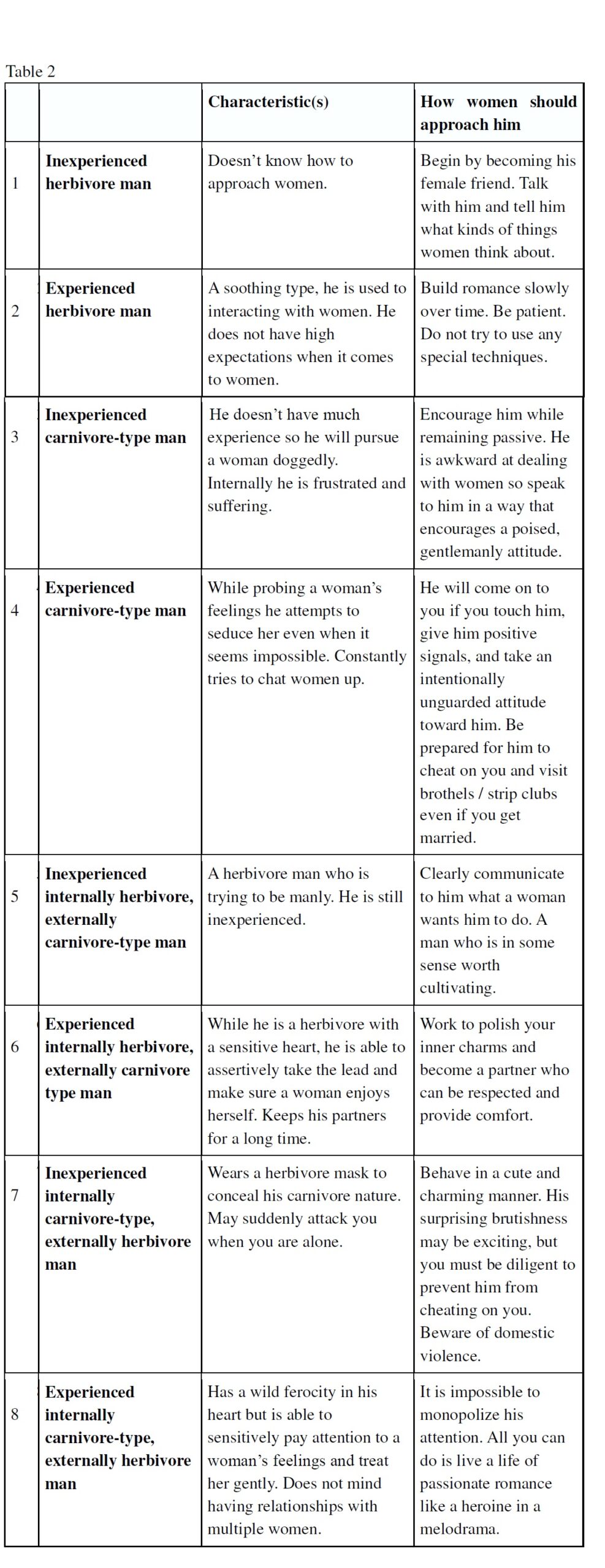

So when it comes to Japan, is the number of herbivore men really increasing? For this, too, there is as yet no positive data whatsoever. The concept of herbivore men did not appear until 2006, so there is no way of gathering data from before this time. But if herbivore men can be interpreted as “men who have lost their ferocity” there is some data that is extremely interesting. Figure 1 on the following page is a chart I made based on one created by behavioral ecologist Hiraiwa-Mariko Hasegawa. It displays the number of men arrested for murder per 100,000 individuals in Japan broken down by age. A curve for 1955, immediately after the war, and a curve for 2000 are shown.

Looking at this graph, two things become apparent. The first is that, over the forty-five years from 1955 to 2000, the number of Japanese men arrested for murder underwent an overwhelming decline. The reduction was particularly sharp in the number of men in their early twenties arrested for this crime (the number of people arrested for murder is believed to closely correspond to the number of murders committed). Over this forty-five year period this number has fallen roughly ninety percent. They are not shown on this graph, but if we look at the numbers for each year over this period we see that this was a continuous decline. The second thing we can see is that in 2000 it was not men in their twenties but men in their thirties who committed the most murders. The fact that it is men in their twenties who commit the most murders, a notable feature of crime statistics, no longer held true in Japan. According to Hasegawa, this is something unique to this country.

In other words, what can be said based on this data is that the ferocity or propensity for violence of Japanese men in their twenties has declined steadily since the end of the war, and is now less than that of men in their thirties. If the herbivorization of men is interpreted as a lessening of their propensity for violence, circumstantial evidence can be obtained in support of this trend. As a result of this fact something even more interesting becomes clear.

According to this graph, the gradual decline in young men’s propensity for violence began at the end of the war. Entering the 21st century the progress of this trend is unmistakeable. Various opinions have been offered on when the herbivorization of young men began. One idea is that it began in the 1980s when women started to advance in society and male power began to diminish. Another hypothesis is that it began during the period of poor economic circumstances in the 1990s. While these factors could of course be considered relevant, what this graph makes clear is something different: the herbivorization of young men in fact began at the end of the war and has continued unabated until the present time. What does this mean?

In the sixty-six years between the end of World War II in 1945 and 2011, Japan did not directly participate in military action either within its own borders or overseas. The nation remade itself on the basis of a new pacifist constitution and abjured direct involvement in military activities. As a result, Japan has enjoyed sixty-six years of peace. The Japanese army (Japan Self-Defense Forces) has not taken part in a single military action since the end of the war. This is a surprising fact, because it means that among all of the current members of the self-defense force there is not a single soldier who has experienced military action on the battlefield as a member of this force. Not only that, but almost none of the people under sixty-five years of age who support Japanese society have experienced war.

What has occurred in this society under these circumstances? To begin with, the “if you are a man you must become a soldier” social norm has disappeared from Japanese society. During the war the idea that “it is natural for men to prepare themselves to be good soldiers and die for their country” existed as a deep-seated social norm. Over the course of the long period of post-war peace this norm disappeared. A soldier’s mission is to slaughter enemy soldiers on the battlefield. In a society at peace there is no need for norms that compel men to bear the burden of this mission. Men are freed from this “you must be a soldier” norm and begin to lose their propensity for violence. This process has progressed over the sixty-six years since the end of the war. As a result, young men of the 21st century have been liberated from this norm.

In other words, the herbivorization of young Japanese men is a byproduct of the Japan’s sixty-six years of peace following World War II. Men who enlist in the Japan Self-Defense Forces can be thought of as a particular type of young man. Joining up isn’t very popular, so recruitment centers have been set up in towns and cities to attract prospective soldiers. Being a member of the Japan Self-Defense Forces does not necessarily mean people will look at you with respect. It is a profession that is neither despised nor particularly respected. In this respect Japan is very different from South Korea. South Korea is in a state of ceasefire and employs a system of conscription. I would suggest that South Korea, unlike Japan, has a society in which the “a man must be a soldier” social norm carries great weight. I wonder how the existence of “herbivore men,” the product of a society that has lost this norm, appears to South Korean eyes? As someone who lives in Japan, this is something I would be very interested to learn.

In any case, if the emergence of herbivore men is a byproduct of Japan’s post-war peace, I think it is something that must be welcomed. There is nothing more valuable than the absence of war. Very few of the young people in today’s Japan have been trained to kill, and none have experienced combat on the battlefield. If they were told to kill a person standing in front of them they would presumably not have any idea how to do so. Of course, there are many brutal crimes such as rape and murder committed in Japan, but in comparison to other countries their number is considered low. I think that one of the reasons for this is that for sixty-six years Japan has not directly taken part in a war and Japanese territory has not been the site of combat. We must not forget that the achievement of Japan’s post-war peace has been made possible by American military power through the treaty of mutual security between the United States and Japan. Herbivore men can also be thought of as a phenomenon arising out of a relative absence of military tension in this country as a result of the balance of power in East Asia between America, Japan, the Korean Peninsula, China, and Taiwan. In this sense herbivore men can be said to be inextricably linked to the question of the precise nature of Japan’s post-war political system.

3. Herbivore Men and Gender

It is important to consider herbivore men from the perspective of gender, because a herbivore man can also be thought of as a man who is attempting to dismantle with his own two hands the machismo-centered norms of manliness that have existed until now. In the interviews I conducted I found that for the most part these young men viewed their own herbivore status positively, but at the same time there were also individuals who were troubled by an awareness of being looked at with contempt by society.

We hear many statements critical of herbivore men being made by men in the mass media and on the Internet. For example, in a TV program broadcast in 2008, an older male announcer said something to the effect of “herbivore men have appeared and young Japanese men have truly become no good.” In everyday conversation, too, the term “herbivore men” is used when young people are criticized for having become weak. Voices can also be heard deploring the fact that university students no longer go abroad to study and new employees refuse to work late and blaming these developments on herbivorization. Young men losing interest in cars and lackluster automobile sales have also been blamed on the herbivorization of the youth. For men in middle-age and older, the herbivorization of young men seems to be seen as something truly deplorable.

I think this feeling of disapprobation on the part of older men comes in two varieties. One type is simply a feeling of regret and sadness that young men have lost their “manliness.” They deplore the fact that young men have lost their masculinity and become effeminate, and that as a result they will be unable to support Japan’s economic growth going forward and the country will succumb to international competition. When it comes to family life they suspect that in the future men will be shamefully henpecked and dominated by their wives. The other type is a form of jealousy. When they themselves were young it was impossible to have a romantic relationship or get married without being “manly,” and if they happened to like cute things or cake it was impossible for them to say so. Today’s young men have broken the spell of “manliness,” and no one condemns them even if they pierce their ears and eat sweets. This is in fact something older men envy. I myself understand this second feeling quite well. I marvel at young men who dress up and adorn themselves without any self-consciousness. I have no desire to criticize herbivore men. I want to cheer them on.

How might herbivore men be viewed when seen from the perspective of feminism? Japan’s contemporary feminism began in the 1970s. A structure exists in which, within both society’s public and private domains, “men” shape norms to which “women” are then subordinate, and a major task of feminism has been to dismantle this structure in all its various dimensions. Viewed from this perspective, I think the appearance of herbivore men can be seen as a victory for feminism; herbivore men are men who feel constricted by a “manliness” that means creating norms and controlling and protecting women and who are attempting to release themselves from its spell. As this comes from an internal motivation and not as the result of condemnation by women, is this not indeed quite close to the new type of man feminism is seeking? I think that for feminists herbivore men can at least be seen as potential allies in the struggle to change this society’s gender order rather than men who must necessarily be treated as adversaries. If even this is disputed, surely it can be said that, from the point of view of feminism, herbivore men are not as bad as the traditional type of man that has been prevalent until now. They want to engage in careful communication with their female partners and make various decisions together. Is this not something feminism has forcefully demanded of men? Of course, the appearance of herbivore men does not mean that society’s gender constructions and norms themselves will be dismantled. But to therefore conclude that because herbivore men are men they can only be seen as vessels of male authority, is, I think, to be excessively in thrall to prejudice.

This is how I see it, but, surprisingly, Japanese feminists have made almost no reference to the herbivore men phenomenon. When it comes to the mass media, magazines, and the Internet, too, with the exception of a very small group of outliers, feminists have remained silent on herbivore men. I find it very strange that feminism, which talks a great deal about gender phenomena, has almost nothing to say about herbivore men. I tried asking feminists I know about herbivore-men, but I did not manage to get much of a response. One feminist angrily exclaimed, “they may be called ‘herbivore men,’ but isn’t domestic violence increasing among young men?” I don’t think domestic violence has increased compared to forty years ago, but she at least seemed to have this sense. Another feminist said, “the phrase ‘herbivore men’ conceals male violence and I find it offensive.” In neither case did the women in question seem to have any affinity for herbivore men.

The sense I got from observing the reaction of feminists was that they think “herbivore men” are a new “trap” created by male power. I suspect that behind this lies a general rule, based on experience, that all attempts by men to get closer to women by saying kind words or taking a sympathetic attitude should be thought of as traps. They perhaps think that my saying “herbivore men are increasing – that’s a victory for feminism, isn’t it?” is just a new smokescreen created by male power to conceal male violence. In any case, unless feminists themselves speak about it in earnest I have no way of knowing what they think about this phenomenon. It may be that feminists do not think the emergence of “herbivore men” is an issue worth addressing. I have not been asked to make comments by academic feminists regarding herbivore men, but I have been asked to share my own thoughts on this phenomenon at local women’s centers on numerous occasions. The women who run these centers are very interested in the herbivore man phenomenon. My speaking events had many participants, most of whom were women. I found it very interesting to see such a large difference in the level of interest between academic feminists and the women at these centers.

The Japanese government has extolled the attainment of a “gender-equal society.” I believe that the number of herbivore men must increase in order to realize this aim. What is good about herbivore men is their desire to decide things together with their female partners through discussion and establishing good lines of communication. Is this not indeed an essential ability required of men when building a gender-equal society? It therefore follows that those who are trying to build this kind of society ought to raise their voices in support of herbivore men.

With this in mind, young women must also reconsider their own expectations of men. According to what young women say and surveys that have been taken of their opinions, when it comes to a male partner a great many of them are looking for a man who is strong-willed, reliable, and will assertively take charge of them. But this desire only reinforces the old gender paradigm in which men are dominant and women are subordinate. It is clearly not an approach that will lead to a society in which both men and women participate as equals. But here extremely difficult problems exist.

For example, among young women there are many who want to be loved and find happiness through a romantic relationship with a man. They dream of being together with a man who actively loves and desires them while they themselves take a passive role. This passive desire places a lot of pressure on the men who are their partners. As the herbivore men stated in their interviews, when women have passive desires it puts men under pressure to actively do something in response, and if only men must take on this obligation it might be better for them not to get involved in romantic relationships at all. As a concrete example of this tendency, in response to a questionnaire 90% of women said that they wanted to be proposed to by a man.12 This can put a lot of pressure on men.

More than a few men wonder sadly why the obligation of proposing must be born only by males. A proposal is a verbal promise to get married, so there should be no problem with it coming from either party, or indeed for a man and a woman to come to the decision to become husband and wife after discussing it with each other. This would create greater gender equality. Nevertheless, the strongest objections to equality between men and women in this area come from the women’s side. It seems that for many women the only conceivable path to marriage involves being proposed to by a man. Of course, it is possible to take the position that considering the heavy burdens of pregnancy/childbirth born by the woman after marriage it is natural for the proposal and a promise to properly protect her during this period come from the man. But I don’t think this protection model is appropriate in a society in which men and women are treated as equals. So what is to be done? I do not have the answer. We must presumably wait for herbivore men and their female partners to create a new paradigm going forward.

In this article I have examined herbivore men in Japan. The phenomenon of herbivore men is an important development that cannot be avoided when considering the transformation of the male gender in this country. As this term appeared only very recently academic research has not yet made much progress, but I think that much can be expected of this line of inquiry in the future. Research comparing Japan to other countries is also work that must be undertaken. These efforts clearly have the potential to provide significant stimulation to the field of international gender studies going forward.

Citations:

Full list of citations for this paper can be found here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314632713_A_Phenomenological_Study_of_Herbivore_Men

References:

Fukasawa, Maki(深澤真紀) 2007 『平成男子図鑑 リスペクト男子とし

らふ男子』日経BP社

Morioka, Masahiro(森岡正博) 2008 『草食系男子の恋愛学』メディアフ

ァクトリー

Morioka, Masahiro(森岡正博) 2009 『最後の恋は草食系男子が持ってく

る』マガジンハウス

Ushikubo, Megumi(牛窪恵) 2008 『草食系男子「お嬢マン」が日本を変

える』 講談社プラスアルファ新書

Editor’s note: Permission to reprint this article was supplied by the author.