According to a recent poll only 18% of U.S. people consider themselves feminist.1 On that account we can expect readers of romance novels to comprise not more than 18% feminists, and likely far less due to the fact that feminists disparage traditional approaches to romance…. at least according to their rhetoric.

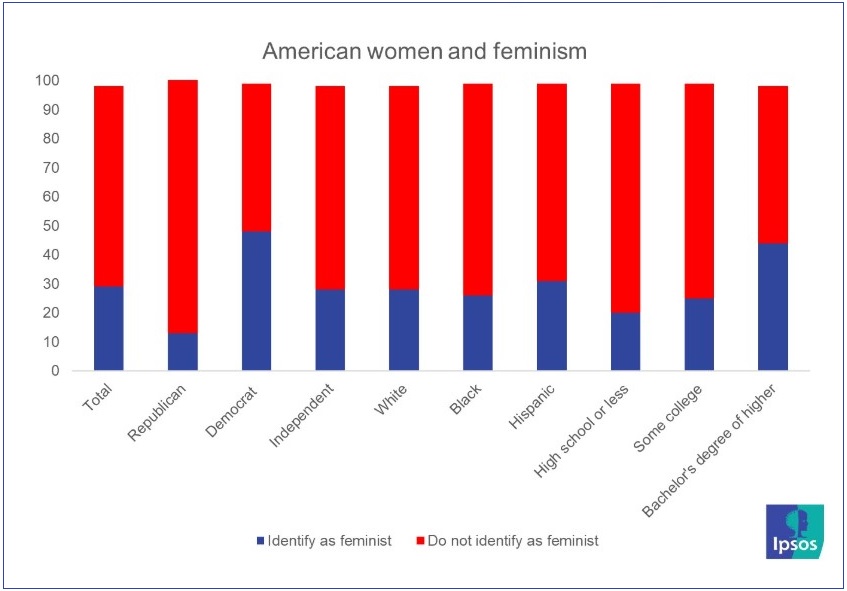

A more generous National Geographic/Ipsos survey2 of more than 1,000 American women found that 29% of respondents identified as feminists. From the study its worth noting, as an aside, the political spread among feminist women, with Republicans scoring low in feminist self-identification, Democrats scoring high, and Independents somewhere in the middle:

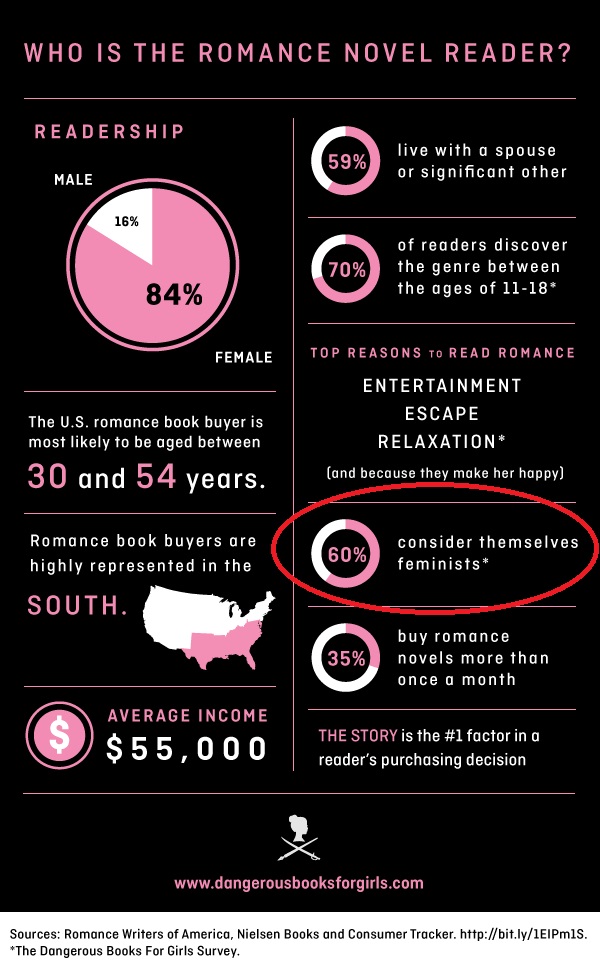

In line with these surveys, we can assume that women who identify as feminist represent less than one third of all women in the USA. With this fact in mind, imagine my surprise when I recently discovered that a whopping 60% of readers of romance novels are feminist, which means that almost two thirds of romantic love enthusiasts are…. feminists! This finding is from a survey of 800 people, which discovered the following details about the average romance reader:3

Author of the survey summarised the question and answers in the following way:

“In the survey of romance readers, I asked if one identified as feminist, believed in equality but wouldn’t use the term feminist – or, not at all. 61% of respondents replied in the affirmative to the first option. While many commentators expressed their ire at the believe-in-equality-but-wouldn’t-use-the-term-feminist option, 35% selected this. Just 3% said not at all (“The third option makes me cry,” one self declared feminist wrote).

The more I read from both sides, the more I realized that we’re more alike than we let on. Whether you call it chivalry or manners, we all want someone to open the door for us.”3

Her last sentence proposes a rationale of (the high number of) feminist readers of romance novels: that they still want doors opened for them, whether actual doors, or doors into better jobs, boardrooms and other kinds of feminist power that are gifted to them by the actions of chivalric men. This point about feminist rationale was confirmed in a study by Gul & Kupfer4 which discovered that feminists felt the positive sides of benevolent sexism outweighed the negatives even if they believed it was somewhat patronising.

Many feminists believe that romantic love is a subversive trope, a positive one that works to increase the power of women relative to men. Elizabeth Reid Boyd, of the School of Psychology and Social Science at Edith Cowan University, and Director of the Centre for Research for Women in Western Australia with more than a decade as a feminist researcher and teacher of women’s studies, tells:

“I muse upon arguments that romance is a form of feminism. Going back to its history in the Middle Ages and its invention by noblewomen who created the notion of courtly love, examining its contemporary popular explosion and the concurrent rise of popular romance studies in the academy that has emerged in the wake of women’s studies, and positing an empowering female future for the genre, I propose that reading and writing romantic fiction is not only personal escapism, but also political activism.

Romance has a feminist past that belies its ostensible frivolity. Romance, as most true romantics know, began in medieval times. The word originally referred to the language romanz, linked to the French, Italian and Spanish languages in which love stories, songs and ballads were written. Stories, poems and songs written in this language were called romances to separate them from more serious literature – a distinction we still have today. Romances were popular and fashionable. Love songs and stories, like those of Lancelot and Guinevere, Tristan and Isolde, were soon on the lips of troubadours and minstrels all over Europe. Romance spread rapidly. It has been called the first form of feminism (Putnam 1970).4

Readers of my writings are familiar with the idea that romantic love and feminism constitute a seamless tradition of gynocentrism that first began in the royal courts of Europe.5 There have occurred transformations in the campaign strategies of feminists throughout the ensuing centuries, but the primary impulse remains consistent through each new generation of feminist activity: to increase the power of women via the institution of a ‘sexual feudalism’ – ie. the proposition that men should act as a quasi serving-class for women.

The following examples of romantic love in Victorian literature are excerpted from the book Male Masochism by Carol Siegal 6. Notice the thematic continuity of this literature with the earlier sexual-relations contract first invented in Medieval Europe:

“A great deal of what [Victorian] women’s literary works had to say about gender relations may have been as disquieting as feminist political manifestos, and ironically so, in that the novels seem most anti-male in the very places where they most affirm a traditionally male vision of love. While women’s lyric poetry tended to reverse the conventional gender roles in love by representing the female speaker as the lover instead of the object of love, women’s fiction most frequently reproduced the images, so common in prior texts by men, of the self-abasing male lover and his exacting mistress.

For example, in Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff declares himself Cathy’s slave; in Jane Eyre, Rochester’s desire for Jane is first inspired and then intensified by his physically dependent position; in Middlemarch, Will Ladislaw silently vows that Dorothea will always have him as her slave, his only claim to her love lies in how much he has suffered for her. In several Victorian novels by women, men must undergo quasi-ritualized humiliation or punishment before being judged deserving of their lady’s attention. For instance, in Olive Schreiner’s Story of an African Farm, the fair Lyndall condescends to treat her admirers tenderly after one has been horsewhipped and the other has dressed himself in women’s clothes to wait on her. Although Victorian women’s novels do explore the emotional insecurities of the heroines, their apparent self-possession is also stressed, in marked contrast to their lovers’ displays of agony, desperation, and wounds.”

The author goes on to say that male masochism and the dominatrix-like behavior of women in much literature is continuous with courtly love literature from the Middle Ages. And whilst some men self-consciously chose their lowly position in relation to women, the men described in Victorian women’s novels lacked such volition and were helplessly controlled by the power of love and beauty:

“These texts also insist that the true measure of male love is lack of volition. While the heroines make choices that define them morally, the heroes are helplessly compelled by love, and not judged to love unless they are helpless. In this respect Victorian women’s fiction recovers the ethos so often expressed in medieval courtly romance that love must be “suffered as a destiny to be submitted to and not denied.” It also departs from the conventions of medieval romance in describing the helpless submission to love as an attribute of true manliness, and thus Victorian women’s fiction directly attacks the degeneration of chivalry into the self-conscious and controlled “gallantry” of eighteenth century libertines.”

Just like their forebears, feminists constitute an army of women working to preserve and extend the tradition of elevated womanhood that has been championed over the last millennium, making the feminist project a remarkably traditional enterprise while putting a lie to its claim to be a forward looking, progressive movement.

The only question left to ask is how, exactly, can this tradition be most accurately characterised? Is it a philosophy, an ideology, human nature, or the slow cultural build-up of behaviorist techniques applied to heterosexual relationships? Its probably a little of all these things, but I’m going to follow the European tradition at the root of romantic love, which saw it primarily as a religion complete with its own guiding Goddess. Her name, as spoken in medieval Germany and through the centuries was Frau Minne.

I have published details about this Goddess before, so rather than rewriting the details I invite the reader to visit the article7 and look further into the essential religiosity at the heart of our gynocentric cult. Furthermore, as recently stated by Alison Tieman, divinity has today become associated with every human woman, imparting to her the power of “I am a Goddess” in much the same way as once done to pharaohs or emperors, or divinised mortals, who became God-men in ancient times and received religious devotion due of a God. That is, half the human population has undergone an apotheosis, while the other half stand in awe and service.

The differences between a god-complex arising variously from a psychotic episode, in cases of extreme narcissism, or in a society that has seen fit to elevate an individual/s to God status is perhaps moot. These things more often appear together, in combinations. Whatever the causes, we are safe to conclude that feminism amounts today to a global religion, one as powerful as any that have gone before it, with women collectively representing the Godhead to an enthralled male audience.

References:

[1] Only 18 percent of Americans consider themselves feminists, Vox 2015

[2] Less than a third of American women identify as feminists

[3] Dangerous Books For Girls: The Bad Reputation of Romance Novels Explained.

[4] Elizabeth Reid Boyd, Romancing Feminism: From Women’s Studies to Women’s Fiction, 2014

[4] Gul, P., & Kupfer, T. R. (2018). Benevolent Sexism and Mate Preferences: Why Do Women Prefer Benevolent Men Despite Recognizing That They Can Be Undermining?. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 0146167218781000.

[5] Damseling, chivalry and courtly love (part two)

[6] Male Masochism by Carol Siegal

[7] ‘Frau Minne’ the Goddess who steals men’s hearts